Love Your Heart

Author: Dr. Stephen Chaney

Heart healthy diets are confusing.

Heart healthy diets are confusing.

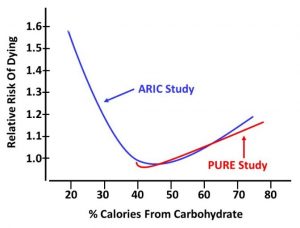

- First, we were told that fats, especially saturated fats, were the problem. Then it was carbohydrates.

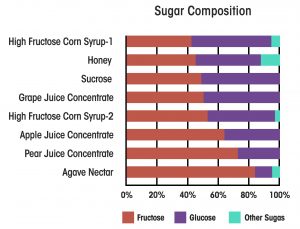

- Then, we were told not all carbohydrates were equally bad for us. Sugars were the culprit.

- Next, we were told not all sugars were bad for us. It was added sugars, especially the sugars added to sodas and other sugary drinks.

- In fact, most of the clinical studies on the bad effects of sugar have been done with sugar-sweetened sodas.

- If sugar-sweetened sodas are the problem, then surely diet sodas must be the answer.

Maybe not. In a previous issue of “Health Tips From The Professor” I summarized studies showing that consuming diet sodas was just as likely to be associated with obesity and diabetes as consuming sugar-sweetened sodas.

But what about heart health? Are diet sodas better for your heart than sugar-sweetened sodas? A recent study (E. Chazelas et al, Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 76: 2175-2180, 2020) suggests the answer is no.

How Was The Study Done?

This study is part of a much larger French study on the effect of diet on health outcomes called the NutriNet-Sante cohort. The NutriNet-Sante cohort study was started in 2009 and, as the name suggests, makes extensive use of online questionnaires. For example:

This study is part of a much larger French study on the effect of diet on health outcomes called the NutriNet-Sante cohort. The NutriNet-Sante cohort study was started in 2009 and, as the name suggests, makes extensive use of online questionnaires. For example:

- Participants are asked to fill out online questionnaires on physical activity, socioeconomic status, anthropometric data (height, weight, etc.), and major health events on a regular basis.

- Every 6 months participants are asked to fill out 3 web-based 24-h dietary records (2 on weekdays and 1 on a weekend).

- Major health events were validated based on their medical records and France’s national health insurance system (Yes, Big Brother is definitely watching in France).

- Deaths were validated using France’s national mortality registry.

The study included a total of 104,760 participants with an average age of 42.9 and an average BMI of 23.7 (towards the upper end of the normal range) and followed them for 10 years. [Note: The average BMI for Americans at age 40 is 28.6, which is towards the upper end of the overweight category.]

The study compared consumption of diet drinks and sugary drinks with first-time cases of heart disease events (stroke, heart attack, angina, and angioplasty) during a 10-year period.

- All first-time cases of heart disease events were combined into a single category for this publication. They will be considered separately in a subsequent publication.

- Artificially sweetened beverages (diet drinks) were defined as beverages containing non-nutritive sweeteners. Sugary drinks consisted of all beverages containing ≥ 5% sugar (sodas, syrups, 100% juice, and fruit drinks).

- For both categories of beverages, the participants were divided into non-consumers, low consumers, and high consumers.

Do Diet Sodas Hurt Your Heart?

The results were clear. When high consumers were compared with non-consumers:

The results were clear. When high consumers were compared with non-consumers:

- High consumers of sugary drinks had a 20% increased risk of first-time heart disease events.

- High consumers of diet drinks had a 32% increased risk of first-time heart disease events.

The authors concluded, “In this cohort, higher intakes of [both] sugary drinks and diet drinks were associated with a higher risk of heart disease, suggesting that artificially sweetened beverages might not be a healthy substitute for sugary drinks.”

I also might point out that if this study had been done in the United States the increased risk of heart disease might have been greater.

That is because the French drink less sugary drinks and diet drinks than Americans.

- High consumers of both sugary drinks and diet drinks in this study averaged 6 ounces per day.

- In contrast, the average consumption sugary drinks in the United States is around 17 ounces per day.

Since consumption of sugary drinks is associated with increased incidence of heart disease and we drink more sugary drinks, the increased risk of heart disease in Americans might be greater than the 20% reported in this study.

What Are The Pros And Cons Of This Study?

On the plus side, this was a very large and well-designed study.

On the plus side, this was a very large and well-designed study.

For example, many studies of this type take a single assessment of the participant’s diet, either at the beginning or end of the study. They have no idea whether the participants changed their diet during the study. This study did a diet assessment every 6 months.

On the minus side, this was an association study. It measured the association of sugary drink and diet drink consumption with heart disease. Association studies have several limitations. Here are the top three:

#1: Confounding variables. Here are a couple of examples:

- People who are overweight tend to drink more diet drinks than people who are normal weight. Obesity increases the risk of heart disease. Therefore, obesity is a confounding variable. You don’t know whether heart disease increased because the participants drank more diet drinks or because they were obese.

- People who consume more diet drinks tend also to eat less healthy diets. Unhealthy diets increase the risk of heart disease. Thus, unhealthy diets are also a confounding variable.

The study authors adjusted for confounding variables by statistically correcting the data for:

- Age, sex, BMI, sugar intake from other dietary sources, smoking status, physical activity, and family history of heart disease.

- Intakes of alcohol, total calories, fruits & vegetables, red & processed meats, nuts, whole grains, legumes, saturated fat, sodium, and proportion of highly processed food in the diet.

- Presence of type 2 diabetes, elevated cholesterol or triglycerides, or high blood pressure upon entry into the study.

In short, they did an excellent job of controlling for confounding variables that also affect the risk of heart disease.

#2: Reverse Causation: This is the chicken and egg question. This study measured the association between sugary and diet drink consumption and heart disease. None of the participants in the study had diagnosed heart disease when the 10-year study began.

However, both obesity and sugar consumption have been linked to increased risk of heart disease. What if some participants in the study had been diagnosed with heart disease early in the study and switched to diet drinks to lose weight or reduce sugar intake?

In that case, the diagnosis of heart disease would have caused increased diet drink consumption rather than the other way around. That would be reverse causation.

The study authors took reverse causation into account by excluding participants who experienced a first-time heart disease event in the first 3 years of this 10-year study. In other words, participants had to have been consuming sugary or diet drinks for at least 3 years before their heart disease event for their data to be included in the analysis.

This is considered the gold standard for reducing the influence of reverse causation on the outcome of the study.

#3: Uncertainty About Causation:

Association studies do not provide information on the possible mechanism(s) of the association.

For example, multiple previous studies have shown that people are just as likely to gain weight and develop type 2 diabetes when they consume diet drinks or sugary drinks. However, after years of study, the mechanism(s) of that effect are uncertain.

- The mechanism may be physiological. However, many physiological mechanisms have been proposed. None have been proven.

- The mechanism may be psychological. We may feel so virtuous for drinking diet drinks that we think it gives us license to eat more junk food. As a former University of North Carolina colleague once put it, “The problem is that we are using our diet drinks to wash down a Big Mac and fries.”

Association studies also do not prove causation. We cannot say with confidence that diet drink consumption increases our risk of heart disease. Nor can we speculate on the mechanism by which this might occur.

However, as the authors of this study concluded, we can say with confidence that there is no evidence that diet drink consumption decreases the risk of obesity, diabetes, or heart disease.

Love Your Heart

Love Your Heart – Drink Water Rather Than Sugar-Sweetened Or Artificially Sweetened Beverages.

If drinking diet drinks does not decrease your risk of heart disease, what can you do to decrease your risk?

If drinking diet drinks does not decrease your risk of heart disease, what can you do to decrease your risk?

The short answer is to fall in love with water. Water has no calories, no sugar, and no artificial sweeteners. In the study described above, it was the non-consumers of sugary beverages and diet beverages that had the lowest risk of heart disease.

Pure water is, of course, the best alternative. However, if plain water is too boring, try herbal teas. If you crave the fizz of sodas, try unsweetened sparkling water, perhaps infused with a little of your favorite fresh fruit. If you crave the caffeine of sodas, coffee or tea might suit you best, preferably without the sugar and cream. There are just two caveats:

- Tea and coffee should not be your only source of liquid.

- It goes without saying that you want to avoid the 500 calorie Starbucks extravaganzas.

Love Your Heart – What About Artificially Sweetened Foods?

If artificially sweetened drinks have no benefit for preventing obesity, diabetes, or heart disease, what about artificially sweetened foods? Do they also have no benefit?

The short answer is that we don’t know. Most of the studies to date have been with artificially sweetened beverages. However, these studies should make us cautious. We should not automatically assume that artificially sweetened foods are beneficial because they contain fewer calories. They may be just as useless as artificially sweetened beverages.

Love Your Heart – A Holistic Approach

With that in mind, here is what the American Heart Association recommends for reducing your risk of heart disease:

- If you smoke, stop.

- Choose good nutrition.

-

- Choose a diet that emphasizes vegetables, fruits, whole grains, low-fat dairy products, poultry, fish, legumes, nuts, and nontropical vegetable oils (ie, avoid coconut and palm oil).

-

- Choose a diet that limits sweets, sugar-sweetened beverages, and red meats.

-

- [Note: Don’t substitute artificially sweetened beverages for sugar-sweetened beverages. That doesn’t appear to offer any advantage. Drink water instead.]

- Reduce high blood cholesterol and triglycerides.

-

- Reduce your intake of saturated fat, trans fat and cholesterol and get moving.

-

- If diet and physical activity don’t get your cholesterol and triglyceride numbers under control, then medication may be the next step.

-

- [Note: The American Heart Association recommends changing your diet and physical activity first and only resorting to medications if lifestyle changes don’t work. Diet and exercise do not have side effects. Medications do.]

- Lower High Blood Pressure.

- Be physically active every day.

- Aim for at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity physical activity per week.

- Aim for a healthy weight.

- Manage diabetes.

- Reduce stress.

- Limit alcohol.

The Bottom Line

Previous studies have shown that people are just as likely to gain weight and develop type 2 diabetes when they consume artificially sweetened and sugar-sweetened drinks. In this issue of “Health Tips From the Professor” I shared a study showing that artificially sweetened drinks are just as bad for your heart as sugar-sweetened drinks.

These are all association studies. Association studies do not provide information on the possible mechanism(s) of the association.

That means we don’t know why artificially sweetened drinks are bad for your heart.

- The mechanism may be physiological. However, many physiological mechanisms have been proposed. None have been proven.

- The mechanism may be psychological. We may feel so virtuous for drinking diet drinks that we think it gives us license to eat more junk food. As a former UNC colleague once put it, “The problem is that we are using our diet drinks to wash down a Big Mac and fries.”

Association studies also do not prove causation. We cannot say with confidence that diet drink consumption increases our risk of heart disease. Nor can we speculate on the mechanism by which this might occur.

However, we can say with confidence that there is no evidence that diet drink consumption decreases the risk of obesity, diabetes, or heart disease.

The authors of this study concluded, “…higher intakes of [both] sugary drinks and diet drinks were associated with a higher risk of heart disease, suggesting that artificially sweetened beverages might not be a healthy substitute for sugary drinks.”

For more details on the study and information on a holistic approach for reducing heart disease risk read the article above.

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This information is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.