What Does It Take to Build Muscle in Your 80s?

Author: Dr. Stephen Chaney

As we age it becomes harder to build muscle, so we start to lose muscle mass and strength, a physiological process called sarcopenia. In last week’s issue of “Health Tips From the Professor” I shared studies showing it was possible to slow, and even reverse, age-related loss of muscle mass in our 60’s and 70’s with the correct combination of resistance exercise, protein, and leucine.

As we age it becomes harder to build muscle, so we start to lose muscle mass and strength, a physiological process called sarcopenia. In last week’s issue of “Health Tips From the Professor” I shared studies showing it was possible to slow, and even reverse, age-related loss of muscle mass in our 60’s and 70’s with the correct combination of resistance exercise, protein, and leucine.

But what about those of us in our 80s? Here recent studies have not been as reassuring. The results have been mixed, with some studies suggesting it is impossible to maintain muscle mass in our 80s.

But we know that it is possible for some people to maintain their muscle mass and accomplish incredible physical feats in their 80s. For example, those of you who are my age or older may remember Jack LaLanne, the so-called “Father of the Fitness Movement” who had a popular fitness show on TV from 1953 to 1985. He celebrated his 80th birthday by swimming one and a half miles in the Long Beach harbor towing 80 rowboats with 80 people in them.

Was Jack LaLanne a “freak of nature” or was it his incredible dedication and focus that allowed him to perform incredible physical feats in his 80’s? After all:

- He ate only whole, unprocessed foods. He did not allow processed foods, fast foods, or convenience foods to cross his lips.

- He did two hours of high-intensity workouts every day until the day before he died at age 96 in 2011.

More important is the question of what his physical feats mean for us. Does his example hold out hopes for all of us who wish to maintain our strength and vigor until the Lord calls us home? Or did he set a standard too high for mere mortals like us to achieve?

That is essentially the question that today’s study (GN Marzuca-Nassr et al, International Journal of Sports Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 34: 11-19, 2024) set out to answer.

The authors postulated that previous studies with subjects in their 80s came up short because they included infirm subjects in their studies and/or the intensity of exercise was too low. This study was designed to overcome those shortcomings.

How Was This Study Done?

The investigators recruited 29 healthy, elderly adults (9 men and 20 women) who were either 65-75 (average age = 68) or over 85 (average age = 87) who were still living in the community rather than being institutionalized for health reasons. The average BMI was 26.4 (moderately overweight) for both groups.

The investigators recruited 29 healthy, elderly adults (9 men and 20 women) who were either 65-75 (average age = 68) or over 85 (average age = 87) who were still living in the community rather than being institutionalized for health reasons. The average BMI was 26.4 (moderately overweight) for both groups.

The participants selected for the study had not engaged in any kind of regular resistance training in the previous 6 months. The study excluded individuals with any kind of heart disease, health conditions, or physical limitations that would prevent them from participating in the resistance exercise training program associated with this study.

Participants were asked to fill in a three-day dietary recall at the beginning and end of the study. They were asked not to change their habitual dietary intake or physical activity during the study The diet recall at the end of the study showed compliance with this request. Their dietary intake was calculated based on the average of the two diet recalls.

No significant difference in macronutrient content of the diet was found between groups. For example, the 65-75 group consumed 1.1 g of protein/kg of body weight/day, and the over 85 group consumed 1.2 g of protein/kg of body weight/day.

Both groups were enrolled in a 3-times/week resistance exercise program for 12 weeks. The exercise training program was designed as follows:

- Warm up consisted of 5-minutes on a cycle ergometer followed by full range of motion upper limb movements and one warm up set on both leg press and leg extension machines.

- This was followed by 4 sets on the leg press and leg extension machines and 2 sets of upper body exercises (chest press, lat pulldown, and horizontal row).

- Cool-down consisted of 5 minutes of stretching exercises.

Just prior to the study, the maximum strength on each exercise machine was determined for each participant. The intensity of their workouts was increased from 60% to 80% of that maximum over the 12 weeks of exercise training.

The outcomes of the study were as follows:

- Quadriceps (the muscles on the front of the thigh) cross-sectional area was measured at the beginning and end of the study.

- Whole body lean mass and appendicular lean mass (The lean mass in legs and arms) were measured at the beginning and end of the study.

- The maximum strength for one repetition on each exercise machine was measured at the beginning and end of the study.

The increase in quadriceps cross-sectional area, lean mass, and strength was compared for the 65-75 group and the over 85 group.

Can You Build Muscle In Your 80s?

At the beginning of the study, the over 85 age group scored lower in every category measured in this study. For example:

At the beginning of the study, the over 85 age group scored lower in every category measured in this study. For example:

- Quadriceps cross-sectional area was 7% less in the over 85 age group than in the 65-75 age group.

- Leg extension strength was 10% less in the over 85 age group than in the 65-75 age group.

This loss of muscle mass and strength is to be expected. Although the over 85 age group was consuming enough protein, they were not exercising on a regular basis. Consequently, they were experiencing sarcopenia, age-related loss of muscle mass.

The results of this 12-week resistance exercise intervention were impressive.

- Quadriceps cross-sectional area increased by 10% in the 65-75 age group and by 11% in the over 85 age group. These increases were not statistically different.

-

- Quadriceps cross sectional area increased for everyone in the study, but the increase varied widely from individual to individual.

-

- The increase varied from 1% to 18% in the 65-75 age group and from 6% to 21% in the over 85 age group.

- Whole body lean muscle mass increased by 2% in both the 65-75 and over 85 age groups.

- Appendicular lean muscle mass (lean muscle mass in the arms and legs) also increased by 2% in both groups.

- Leg extension strength increased by 38% in the 65-75 age group and by 46% in the over 85 age group.

-

- Once again, the increase in leg extension strength varied considerably from individual to individual. The increase varied from 5% to 76% in the 65-75 age group and from 26% to 70% in the over 85 age group.

- Similar results were seen for leg press, lat pull down, chest press, horizontal row, and grip strength.

The authors concluded, “Prolonged [12 week] resistance exercise training increases muscle mass, strength, and physical performance in the aging population, with no differences between 65-75 and 85+ adults. The skeletal muscle adaptive response to resistance exercise training is preserved even in male and female adults older than 85 years.”

What Does It Take To Build Muscle In Your 80s?

Why did this study show a benefit of resistance exercise for building muscle mass in octogenarians when previous studies have come up short? The authors postulated this was due to differences in the subjects included in the study and the intensity, frequency, and duration of resistance exercise.

Why did this study show a benefit of resistance exercise for building muscle mass in octogenarians when previous studies have come up short? The authors postulated this was due to differences in the subjects included in the study and the intensity, frequency, and duration of resistance exercise.

- This study included only healthy, community dwelling seniors who could engage in a rigorous training program. Some previous studies included institutionalized seniors who may have been less healthy and more frail.

- The resistance exercise training used in this study involved multiple sets on exercise machines three times a week at 60-80% of maximum intensity for a total of 12 weeks. Previous studies included 1-2 sets, once or twice a week, at lower intensity, and for a shorter duration.

Much more research needs to be done, but the take-home lessons appear to be:

1) It is possible to increase muscle mass in your 80s with sufficient protein and a sufficiently intense resistance exercise program.

2) Not every 80-year-old adult will be able to increase their muscle mass. At the very least, this and previous studies suggest that frail, institutionalized men and women in their 80s may not be able to increase their muscle mass.

-

- Whether this is because their health conditions interfere with their muscle’s ability to build muscle, or they are simply unable to perform the high intensity exercises required to build muscle mass in their 80’s is unclear. More research is needed. While everyone in this study increased muscle mass and strength, the increase varied widely from individual to individual (see above).

My guess is that some of the people in the study did not get enough protein in their diet to support an increase in muscle mass at 85 and older. The over 85 group averaged 1.2 gm of protein/kg body weight/day, but their intake ranged from 0.8gm/kg/day to 1.6 gm/kg/day.

However, the difference in gain of muscle mass and strength could have been due to almost anything. Unfortunately, this study was too small to reliably determine what caused the differences in response to the resistance training.

3) It may require a high intensity resistance exercise program to increase muscle mass in your 80s. Unfortunately, there are very few studies like this for people in their 80s. All we know is that this was a high intensity, high frequency, and long duration resistance exercise program, and it worked. Studies with lower intensity exercise programs have not worked. But nobody has done a study comparing the effectiveness of different intensity exercise programs for people in their 80s.

4) There are too few studies on what it takes for people in their 80s and beyond to stay fit and healthy. The authors of this report argued that this information is vital for guiding government programs designed to support an aging population. It is equally important for all of us who want to remain fit and healthy in our 80s and beyond.

What Does This Study Mean For You?

In my previous “Health Tips From the Professor” I have discussed multiple studies looking at sarcopenia or age-related muscle loss.

In my previous “Health Tips From the Professor” I have discussed multiple studies looking at sarcopenia or age-related muscle loss.

The bad news is that we start losing muscle mass and strength around age 50, and the rate of decline starts to accelerate in our 60s and beyond. This is a normal part of aging. It affects all of us. And if left unchecked, it can have devastating effects on our quality of life in our golden years.

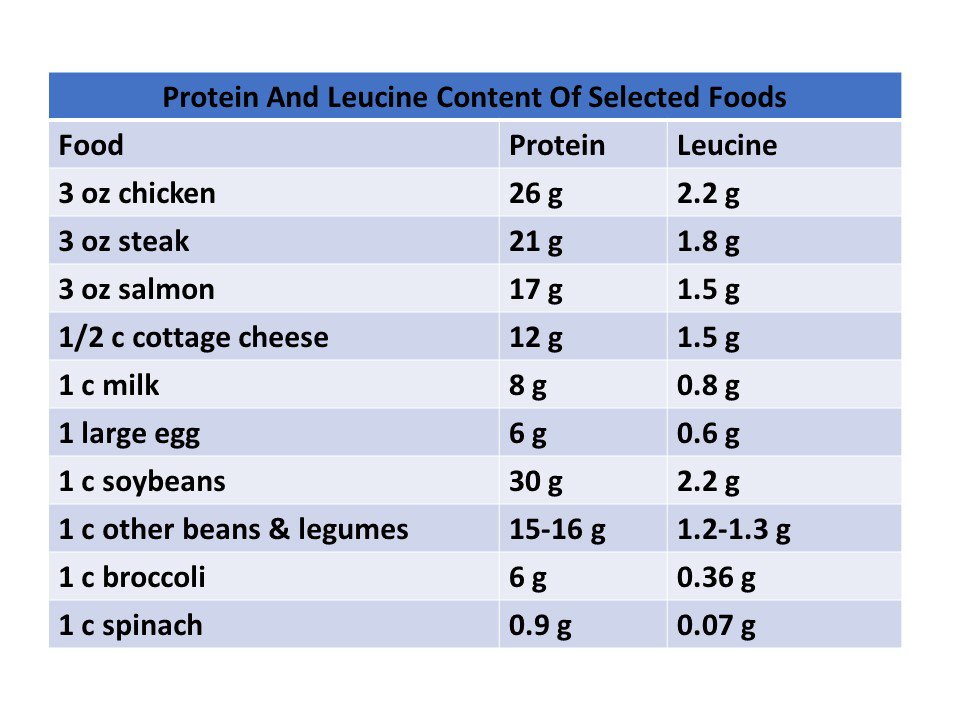

The good news is that we can slow and even reverse the age-related loss of muscle mass by a combination of adequate intake of protein, adequate intake of the essential amino acid leucine, and resistance exercise. Leucine intake is usually adequate when we rely on animal proteins as our main protein source but may be a concern if we rely primarily on plant proteins. So, let’s take a deeper look at protein and exercise requirements.

- We need more protein to build muscle in our golden years than we did in our 30s. If you want more information on the studies supporting that statement, go to https://chaneyhealth.com/healthtips/ and type sarcopenia in the search box. Most experts in this field of study recommend around 1.2 gm of protein/kg of body weight/day rather than the RDA of 0.8 gm of protein/kg of body weight/day for people 65 or older who wish to maintain or increase muscle mass. This study suggests that 1.2 gm/kg/day is also sufficient for people who are 85 and older.

Previous studies have shown that the protein is best utilized to preserve muscle mass when it is spread evenly through the day. That is a concern because many seniors get most of their protein in the evening meal. The article I shared last week showed that adding 20 grams of supplemental protein to the low-protein meals (typically breakfast and/or lunch) was sufficient to balance protein intake and minimize age-related muscle loss.

[Note: To help you with the calculations, 1.2 gm of protein/kg of body weight/day is equal to 0.54 gm of protein/pound of body weight/day. Some quick calculations show that amounts to 78 grams if you weigh 140, 95 grams if you weigh 170, and 112 grams if you weigh 200. Or to simplify, that amounts to 25-30 grams of protein/meal for most people – more if you weigh above 170 pounds.]

2) We need a higher intensity of resistance exercise to build muscle in our golden years than  we did in our 30s. Several previous studies have hinted at that possibility. This study shows that a high intensity resistance exercise program is effective at building muscle mass for people 85 and above. Previous studies suggest that lower intensity exercise programs are not effective in this age group.

we did in our 30s. Several previous studies have hinted at that possibility. This study shows that a high intensity resistance exercise program is effective at building muscle mass for people 85 and above. Previous studies suggest that lower intensity exercise programs are not effective in this age group.

This is an important finding because it is opposite to the usual recommendations for this age group. In the words of the authors, “At an advanced age, people are generally recommended to partake in low-intensive physical activities. We strongly advocate that resistance exercise should be promoted without restriction to support more active, healthy aging.”

Of course, the caveat is that this study excluded frail, institutionalized adults and people with health or physical limitations that would prevent them from participating in a high-intensity resistance exercise program.

So, here are my recommendations:

- Discuss your desire to implement a high intensity resistance exercise program with your health professional. Ask them about any health issues or physical limitations that would affect the exercises you choose.

- Ask your health professional to refer you to a physical therapist to design a high-intensity exercise program you can do at home that is appropriate to your health and physical condition. If the referral comes from your health professional, these sessions may be covered by insurance.

- If you want to utilize the exercise equipment in a gym, start by having a personal trainer knowledgeable about working with people like you design a workout program for you. My personal preference is to continue working with a personal trainer who challenges me to maximize the intensity of my training while taking into account any temporary physical limitations I may be experiencing.

Finally, I recognize that the exercise program described in this study may be too intense for many of my readers. But I also suspect that none of you want to become so frail you can’t enjoy your golden years. So, do what you can. But do something.

The Bottom Line

Most Americans lose lean muscle mass as they age, a physiological process called sarcopenia. This loss of muscle mass leads to reduced mobility, a tendency to fall (which often leads to debilitating bone fractures) and a lower metabolic rate – which leads to obesity and all the illnesses that go along with obesity.

Fortunately, sarcopenia is not an inevitable consequence of aging. There are 3 things we can do to prevent it.

- Optimize resistance exercise training.

- Optimize protein intake.

- Optimize leucine intake.

Last week I talked about optimizing protein and leucine intake. This week I review an article that compared the effectiveness of a 12-week high intensity resistance exercise program for increasing muscle mass and strength with people in the 65-75 age group with those who were age 85 and above.

The results of this 12-week resistance exercise intervention were impressive.

- Quadriceps cross-sectional area increased by 10% in the 65-75 age group and by 11% in the over 85 age group. These increases were not statistically different.

- Whole body lean muscle mass increased by 2% in both the 65-75 and over 85 age groups.

- Leg extension strength increased by 38% in the 65-75 age group and by 46% in the over 85 age group.

- Similar results were seen for leg press, lat pull down, chest press, horizontal row, and grip strength.

The authors concluded, “Prolonged [12 week] resistance exercise training increases muscle mass, strength, and physical performance in the aging population, with no differences between 65-75 and 85+ adults. The skeletal muscle adaptive response to resistance exercise training is preserved even in male and female adults older than 65 years.”

“At an advanced age, people are generally recommended to partake in low-intensive physical activities. We strongly advocate that resistance exercise should be promoted without restriction to support more active, healthy aging.”

For more details about the study and what it means for you, read the article above.

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This information is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.

______________________________________________________________________________

My posts and “Health Tips From the Professor” articles carefully avoid claims about any brand of supplement or manufacturer of supplements. However, I am often asked by representatives of supplement companies if they can share them with their customers.

My answer is, “Yes, as long as you share only the article without any additions or alterations. In particular, you should avoid adding any mention of your company or your company’s products. If you were to do that, you could be making what the FTC and FDA consider a “misleading health claim” that could result in legal action against you and the company you represent.

For more detail about FTC regulations for health claims, see this link.

https://www.ftc.gov/business-guidance/resources/health-products-compliance-guidance

______________________________________________________________________

About The Author

Dr. Chaney has a BS in Chemistry from Duke University and a PhD in Biochemistry from UCLA. He is Professor Emeritus from the University of North Carolina where he taught biochemistry and nutrition to medical and dental students for 40 years. Dr. Chaney won numerous teaching awards at UNC, including the Academy of Educators “Excellence in Teaching Lifetime Achievement Award”. Dr Chaney also ran an active cancer research program at UNC and published over 100 scientific articles and reviews in peer-reviewed scientific journals. In addition, he authored two chapters on nutrition in one of the leading biochemistry text books for medical students.

Dr. Chaney has a BS in Chemistry from Duke University and a PhD in Biochemistry from UCLA. He is Professor Emeritus from the University of North Carolina where he taught biochemistry and nutrition to medical and dental students for 40 years. Dr. Chaney won numerous teaching awards at UNC, including the Academy of Educators “Excellence in Teaching Lifetime Achievement Award”. Dr Chaney also ran an active cancer research program at UNC and published over 100 scientific articles and reviews in peer-reviewed scientific journals. In addition, he authored two chapters on nutrition in one of the leading biochemistry text books for medical students.

Since retiring from the University of North Carolina, he has been writing a weekly health blog called “Health Tips From the Professor”. He has also written two best-selling books, “Slaying the Food Myths” and “Slaying the Supplement Myths”. And most recently he has created an online lifestyle change course, “Create Your Personal Health Zone”. For more information visit https://chaneyhealth.com.

For the past 45 years Dr. Chaney and his wife Suzanne have been helping people improve their health holistically through a combination of good diet, exercise, weight control and appropriate supplementation.