Omega-3 Confusion

Author: Dr. Stephen Chaney

This article includes updates as of October 2, 2018. First, here is the earlier information.

Do omega-3s reduce heart disease risk?

Do omega-3s reduce heart disease risk?

Perhaps there is nothing more controversial in nutrition today than omega-3 fatty acids and heart disease risk. It is so confusing. One day you are told they reduce heart disease risk. The next day you are told they are worthless.

The controversy around omega-3s and heart disease risk is part of the larger controversy around supplementation. It is omega-3 supplements that are controversial, not omega-3-rich fish. Of course, that completely ignores the fact that many omega-3-rich fish are contaminated with PCBs and/or heavy metals.

Why is omega-3 supplementation so controversial? The problem is that proponents of omega-3 supplementation often seize on a single study as “proof” that everyone should supplement with omega-3s. Opponents of omega-3 supplementation take the opposite approach. They pick studies showing that not everyone benefits from omega-3 supplementation as “proof” that nobody benefits. As usual, the truth is in between.

I have a section in my book, “Slaying The Food Myths,” called “None of Us Are Average.” In that section I point out that clinical studies report the average results of everyone in the study, but nobody in the study was average.

For example, let’s say the study reported that (on average) there was no heart health benefit from omega-3 supplementation. That is what makes the headlines. That is what opponents of omega-3 supplementation cite as “proof” omega-3 supplementation doesn’t work.

However, some of the people in the study may have benefited from omega-3 supplementation, while others did not. Thus, the important question is not “Does everyone benefit from omega-3 supplementation?” It is “Who benefits from omega-3 supplementation?” and “Why do the results vary so much from study to study?”

Omega-3 Confusion

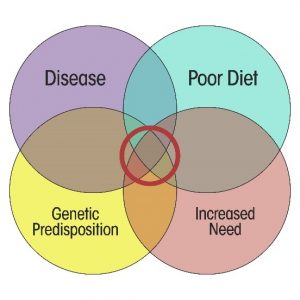

I have a chapter in my book called “What Role Does Supplementation Play?” which helps put this omega-3 controversy into perspective. I created the graphic on the left to answer the question “Who needs supplementation?”

I have a chapter in my book called “What Role Does Supplementation Play?” which helps put this omega-3 controversy into perspective. I created the graphic on the left to answer the question “Who needs supplementation?”

The concept is simple. Poor diet, increased need, genetic predisposition, and pre-existing disease all increase the likelihood that supplementation will be beneficial. However, the benefit will be most obvious in the center of the diagram where two or more of these factors overlap.

Let’s take this concept and apply it to studies of omega-3 fatty acids and heart disease risk. In particular, let’s use this concept to understand what I call “omega-3 confusion” – why some studies give negative results and others give positive results:

Poor Diet: Again, the concept is simple. You are most likely to see a benefit of omega-3 supplementation when the dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids is low. Put another way, if the subjects in a study are already getting plenty of omega-3s from their diet, supplementing with omega-3s is unlikely to provide any benefit.

Until recently, dietary surveys were the standard method for assessing dietary omega-3 intake. However, dietary surveys can be inaccurate. The best of recent studies, measure the omega-3 levels in cellular membranes. The omega-3 levels at the beginning of the study reflect your diet. The omega-3 levels at the end of the study reflect how effective supplementation was at improving your omega-3 status. In short, this is the gold standard for omega-3 clinical studies. Subjects can lie about how many omega-3-rich foods they eat and whether they take their supplements, but the omega-3 levels in their cell membranes reveal the truth.

When you read the methods section, it turns out that most negative studies did not ask how much omega-3s their subjects were getting from their diet. Almost none of the negative studies measured omega-3 levels in cell membranes.

Increased Need: In terms of heart disease, we can think increased need as the presence of risk factors for heart disease such as:

- Age

- Obesity

- Inactivity

- Elevated cholesterol or triglycerides

- Dietary factors like saturated fats and/or sugar and refined carbohydrates

- Smoking

What does this mean in terms of clinical studies?

- Studies in which most of the subjects have a poor diet, are over 65, and have multiple risk factors for heart disease are more likely to show a beneficial effect of omega-3s on heart disease risk.

- Studies in which most of the subjects are young and healthy are unlikely to show a measurable benefit of omega-3s on heart disease risk. You would need to follow this population group 20, 30, or 40 years to demonstrate a benefit.

Genetic Predisposition: There is a lot we don’t know about genetic predisposition for heart disease. The only exception is family history. If you  have a family history of early heart disease, you can be pretty certain you are at high risk for heart disease. As you might suspect:

have a family history of early heart disease, you can be pretty certain you are at high risk for heart disease. As you might suspect:

- Studies focused on populations with genetic predisposition to heart disease are more likely to show a benefit of omega-3 supplementation.

- Studies that just look at the general population without consideration of genetic predisposition to heart disease are less likely to show a benefit of omega-3 supplementation.

Disease: Diseases like diabetes and high blood pressure increase heart disease risk. And, of course, pre-existing heart disease, especially a recent heart attack, dramatically increase the risk of a subsequent heart attack or stroke. Studies focusing on subjects with diabetes have been inconsistent. However, studies focusing on patients with pre-existing heart disease are more clear-cut:

- Studies focused on populations with pre-existing heart disease and/or a recent heart attack are more likely to show a benefit of omega-3 supplementation.

- Studies that just look at the general population without consideration of genetic predisposition to heart disease are less likely to show a benefit of omega-3 supplementation.

Interestingly, the situation is very similar with statin drugs. As I reported in a recent issue of “Health Tips From the Professor” on cholesterol lowering drugs, studies done with patients who had recently had a heart attack show a clear benefit of statin drugs, while studies with the general population show little or no benefit of statin drugs.

One More Factor: There is one more confounding factor that is somewhat unique to the omega-3-heart disease studies and, therefore, not included in the figure at the beginning of this section. Ethical considerations dictate that the placebo group in a double-blind, placebo controlled clinical study receive the “standard of care” for that disease. In the case of heart disease, the standard of care is 4-5 drugs which provide most of the same benefits as omega-3 fatty acids (although with many more side effects).

Thus, these studies are no longer asking whether omega-3s reduce heart disease risk. They are asking whether omega-3s have any additional benefits for heart disease patients already on 4-5 drugs. I have discussed this in more detail in a previous issue of “Health Tips From the Professor” on omega-3 and heart disease.

Why Are Omega-3 Studies Conflicting? In summary, the likelihood that clinical studies show a beneficial effect of omega-3 fatty acids on heart disease risk is highly dependent on study design and the population group included in the study. Many of the studies currently in the scientific literature are flawed in one way or another. Once you understand that, it is obvious why there are so many conflicting studies in the literature.

Why Are Omega-3 Studies Conflicting? In summary, the likelihood that clinical studies show a beneficial effect of omega-3 fatty acids on heart disease risk is highly dependent on study design and the population group included in the study. Many of the studies currently in the scientific literature are flawed in one way or another. Once you understand that, it is obvious why there are so many conflicting studies in the literature.

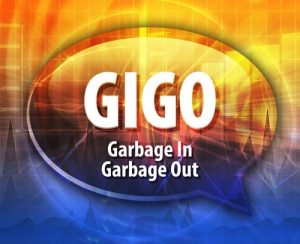

Unfortunately, meta-analyses that combine data from many studies are no better than the individual studies they include in the analysis. It is the old “Garbage in – garbage out” principle.

What Does An Ideal Study Look Like? In my opinion, an ideal study to evaluate the effect of omega-3s on heart disease risk should (at minimum):

- Determine omega-3 levels in cellular membranes as a measure of omega-3 status (dietary intake of omega-3s plus their utilization by the body). The percentage of omega-3 fatty acids in cell membranes is referred to as Omega-3 Index. Based on previous studies (W.S. Harris et al, Atherosclerosis, 262: 51-54, 2017, most experts consider an Omega-3 Index of 4% to be low and an Omega-3 Index of 8% to be optimal.

- Focus on a population group at high risk for heart disease or include enough subjects in the study so that you can determine the effect of omega-3s on high risk subgroups.

- Measure cardiovascular outcomes (heart attack, stroke, cardiovascular deaths, etc.).

- Perform the study long enough so that you can accumulate a significant number of cardiovascular events.

- Include enough subjects for a statistically significant conclusion.

Do Omega-3s Reduce Heart Disease Risk?

Most of you have probably heard of the Framingham Heart Study. It was started in 1941 with a large group of residents of Framingham Massachusetts and surrounding areas. The data from this study over the years has shaped much of what we know about cardiovascular risk factors. The original participants have passed on, but the study has continued with their offspring, now in their 60s.

Most of you have probably heard of the Framingham Heart Study. It was started in 1941 with a large group of residents of Framingham Massachusetts and surrounding areas. The data from this study over the years has shaped much of what we know about cardiovascular risk factors. The original participants have passed on, but the study has continued with their offspring, now in their 60s.

A recent study (W. H. Harris et al, Journal of Clinical Lipidology, doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2018.02.010 ) with 2500 subjects in the Offspring Cohort of the Framingham Heart Study incorporates many of characteristics of a good omega-3 clinical study.

- The average age of the subjects was 66. While none of the subjects enrolled in the study had been diagnosed with heart disease at the time the study began, this is a high-risk population. At this age a significant percentage of them would be expected to develop heart disease over the next few years.

- The subjects did have other risk factors for heart disease. 13% of them had diabetes, 44% had high blood pressure, and 40% of them were on cholesterol medication. However, those risk factors were corrected for in the data analysis, so they did not influence the results.

- The Omega-3 Index was measured in their red blood cell membranes at the beginning of the study.

- The study was long enough (7.3 years) for cardiovascular disease to develop.

When they compared subjects with the highest Omega-3 Index (>6.8%) with those with the those with the lowest Omega-3 Index (<4.2%):

- Death from all causes was reduced by 34%

- Incident cardiovascular disease was reduced by 39% (Remember that none of the subjects had been diagnosed with heart disease at the beginning of the study. This terminology simply means that they received a new diagnosis of heart disease during the study.)

- Cardiovascular events (primarily heart attacks) were reduced by 42%

- Strokes were reduced by 55%.

There were two other interesting observations from the study:

- There was no correlation between serum cholesterol levels and heart disease in this study.

- The authors estimated that it would require an extra 1300 mg of omega-3s/day, either from a serving of salmon or from fish oil supplements, to bring the membrane Omega-3 Index from the lowest level in this study to an optimal level.

The authors cited three other recent studies performed in a similar manner that have come to essentially the same conclusion. These studies are not perfect. They are all association studies, so they do not prove cause and effect.

However, the authors concluded that Omega-3 Index should be measured routinely as a risk factor for heart disease and should be corrected if it is low.

The Bottom Line:

Perhaps there is nothing more controversial in nutrition today than omega-3 fatty acids and heart disease risk. It is so confusing. One day you are told they reduce heart disease risk. The next day you are told they are worthless. I have discussed the reasons for the conflicting results and the resulting omega-3 confusion in the article above.

I shared a recent study that escapes many of the pitfalls of previous studies because it measures the Omega-3 Index of red blood cells as an indication of omega-3 status.

When the study compared subjects with the highest Omega-3 Index (>6.8%) with those with the those with the lowest Omega-3 Index (<4.2%):

- Death from all causes was reduced by 34%

- Incident cardiovascular disease was reduced by 39% (Remember that none of the subjects had been diagnosed with heart disease at the beginning of the study. This terminology simply means that they received a new diagnosis of heart disease during the study.)

- Cardiovascular events (primarily heart attacks) were reduced by 42%

- Strokes were reduced by 55%.

There were two other interesting observations from the study:

- There was no correlation between serum cholesterol levels and heart disease in this study.

- The authors estimated that it would require an extra 1300 mg of omega-3s/day, either from a serving of salmon or from fish oil supplements, to bring the membrane Omega-3 Index from the lowest level in this study to an optimal level.

The authors concluded that Omega-3 Index should be measured routinely as a risk factor for heart disease and should be corrected if it is low.

Are Omega-3s Worthless?

Recommendations from the medical industry changes often. The following updates are in response to some of those changes concerning omega-3 and heart disease. These updates were added on October 2, 2018.

Recommendations from the medical industry changes often. The following updates are in response to some of those changes concerning omega-3 and heart disease. These updates were added on October 2, 2018.

The internet is abuzz with headlines saying things such as “Omega-3 Supplements Don’t Protect Against Heart Disease” and “Forget Omega-3s”. Are those headlines true? Should we throw our omega-3 supplements in the trash?

If the recent headlines are true, it is confusing, to say the least. In the late 90s and early 2000s we were being told of clinical studies showing that omega-3s reduced the risk of heart attack and stroke. At that time the American Heart Association was recommending omega-3 supplements for patients at high risk of heart attack or stroke. What has changed?

It turns out that a lot has changed. The design of clinical studies has changed dramatically in the past 10-15 years. I have covered the changing omega-3 story in detail in my upcoming book “Slaying The Supplement Myths.” Let me just summarize a few key differences between the year 2000 and today.

- The definition of “high risk of heart attack and stroke” has changed dramatically since 2000. Clinical studies today include subjects who have a much lower risk of heart attack and stroke. That makes it more difficult to see any benefits of omega-3s.

- Most studies do not measure the omega-3 status of their subjects. That means they do not know whether their patients were omega-3 deficient at the beginning of the study. It also means they have no objective measure of how faithfully the subjects took their omega-3 capsules.

- We are asking a totally different question today than we were in the year 2000. It is considered unethical to withhold “standard medical care” from the control group. In 2000 the standard of care was one or two heart medications and often did not include a statin. Back then we were asking “Do omega-3s reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke?” Today, the standard of care is 3-5 heart medications, each of which provides some of the same benefits as omega-3s. Today we are asking the question “Do omega-3s provide any additional benefit for people who are already taking 3-5 heart medications?”

Let me start by analyzing a recent study that illustrates these points perfectly.

How Was The Study Done?

On the surface the study appeared to be a well-designed study. The study (The ASCEND Study Collaborative Group, New England Journal Of Medicine, DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804989, 2018 ) was conducted by scientists from the University of Oxford. They used a national diabetes registry and contacted general practitioners from all over England to identify 15,480 patients who had diabetes, but no evidence of heart disease and were willing to participate in the study. Participants were at least 40 (average age 63) and 60% male.

On the surface the study appeared to be a well-designed study. The study (The ASCEND Study Collaborative Group, New England Journal Of Medicine, DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804989, 2018 ) was conducted by scientists from the University of Oxford. They used a national diabetes registry and contacted general practitioners from all over England to identify 15,480 patients who had diabetes, but no evidence of heart disease and were willing to participate in the study. Participants were at least 40 (average age 63) and 60% male.

The participants were mailed a six month’s supply of capsules containing either 1 gram of omega-3s or olive oil as a placebo. Each 6 months the participants were mailed a questionnaire to report on whether they took the capsule daily and whether they had any adverse side effects. If they returned the questionnaire, they were given another 6 month’s supply of omega-3s or placebo. The patients were followed for an average of 7.4 years and “adverse vascular events” (simple definition: non-fatal and fatal heart attack or stroke) were recorded.

Omega-3 and Heart Disease?

The authors of the study reported:

The authors of the study reported:

- Omega-3 supplementation had no significant effect on either serious vascular events or death from any cause.

The authors concluded “These findings, together with results of earlier randomized trials involving patients with and without diabetes, do not support the current recommendations for routine dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids to prevent vascular events.”

On the surface, this appears to be a strong study and the results were conclusive. What could go wrong? The answer is “Plenty.”

What Are The Weaknesses Of The Study?

The study contains multiple weaknesses that have been ignored by the medical community and the press.

The study contains multiple weaknesses that have been ignored by the medical community and the press.

Omega-3 Supplements Reduced Vascular Deaths In This Study. To begin with, the study showed that omega-3 supplementation reduced vascular deaths (simple definition: fatal heart attacks and stroke) by 18%. That observation was reported as a single sentence in the Results section of the paper but did not appear in either the Discussion or Abstract. It was also not reported in any of the media reports telling you that omega-3s are worthless. Perhaps it did not match the preconceived beliefs of the authors.

This Study Was Not Really Looking At High Risk Patients. The studies in the late 90’s and early 2000’s showing a significant effect of omega-3s on heart attack risk were done with truly high-risk patients. For example, the best of these studies looked at the effect of omega-3 supplementation in patients who had suffered a heart attack in the past 6 months. Those patients were at high risk of a second heart attack in the next 6-12 months. They were in imminent danger.

This study looked at patients with diabetes. They have a 2 to 3-fold risk of heart attack or stroke over the next decade. That’s a big difference. In addition, this study only looked at patients with diabetes AND no evidence of heart disease. Their risk of heart attack and stroke is substantially less. In fact, if you look at the data in the study, 83% of the participants in their study were at low to moderate risk of heart disease. Only 17% were at high risk.

To put that into perspective, it has only been possible to prove the effectiveness of statins when they are tested in patients who have already suffered a heart attack. In low risk populations, their benefit is almost negligible. You will find details about those studies in my new book “Slaying The Supplement Myths.”

If you can’t prove statins are effective in low risk populations, why would you expect to be able to show omega-3s are effective in low risk populations.

The Subjects Were Already Getting Near Optimum Amounts of Omega-3s From Their Diet. The study analyzed the omega-3 index (a measure of omega-3 status) from a randomly selected subset of participants at the beginning and end of the study. They reported that the omega-3 index in their study participants increased from 7.1% at the beginning to 9.1% at the end, a 32% increase. They considered that to be a good thing because it showed that their participants were taking the omega-3 supplements faithfully.

The Subjects Were Already Getting Near Optimum Amounts of Omega-3s From Their Diet. The study analyzed the omega-3 index (a measure of omega-3 status) from a randomly selected subset of participants at the beginning and end of the study. They reported that the omega-3 index in their study participants increased from 7.1% at the beginning to 9.1% at the end, a 32% increase. They considered that to be a good thing because it showed that their participants were taking the omega-3 supplements faithfully.

However, let’s put that into perspective. An omega-3 index of 4% is associated with a high risk of heart disease. An omega-3 index of 8% is associated with a low risk of heart disease. It is considered optimum. With an omega-3 index of 7.1% at the beginning of the study, the subjects already had near optimum omega-3 status before the study even began.

If the subjects were already at near optimum omega-3 status, why would you expect additional omega-3 supplementation to be beneficial?

The Subjects Were On 3-5 Heart Medications. To discover this, you had to dig a little. Something only a science-wonk like me is willing to do. The Results section reported that 35% of the subjects were taking aspirin and 75% were on a statin. You have to go to the Supplementary Data online to discover that most of the subjects were on 3-5 heart medications in addition to 1 or 2 medications for diabetes. That is somewhat curious because nobody in the study had any detectable cardiovascular disease.

To understand the significance of this observation, we look at what the drugs do. Aspirin prevents blood clot formation in our arteries, which is one of the main benefits of omega-3s. For reasons nobody understands, statins decrease inflammation, which is another major benefit of omega-3s. Most of the subjects were also taking a medicine to decrease blood pressure, another major benefit of omega-3s.

If subjects are already on 3-5 heart medications that duplicate the benefits of omega-3s, why would you expect omega-3 supplementation to be beneficial?

As I said before, we are now asking a totally different question than we were in the studies performed in the late 90s and early 2000s. Back then we were asking whether omega-3s reduced the risk of heart disease. Today we are asking whether omega-3s have any additional benefits for someone who is already on 3-5 heart medications. That question may be of interest to your doctors, but it is probably not the question most of you are interested in.

Even worse, every one of those drugs has documented side effects. For example, the same group that published this paper also examined the role of aspirin in reducing heart attacks in the same patient population and concluded that the befits of aspirin were “largely counterbalanced by the bleeding hazard [caused by aspirin use],” (The ASCEND Study Collaborative Group, New England Journal Of Medicine, DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804988, 2018). In contrast, they found no side effects in the group receiving 1 gram/day of omega-3s.

Garbage In Again, Garbage Out Again

Two recent meta-analyses (T Aung et al, JAMA Cardiology 3: 225-234, 2018 and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews ) have analyzed all the recent placebo-controlled studies and have concluded that omega-3s are of little or no use for reducing heart disease risk. However, those meta-analyses both suffered from what, in the computer programming world, is called “Garbage in. Garbage out.”

Two recent meta-analyses (T Aung et al, JAMA Cardiology 3: 225-234, 2018 and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews ) have analyzed all the recent placebo-controlled studies and have concluded that omega-3s are of little or no use for reducing heart disease risk. However, those meta-analyses both suffered from what, in the computer programming world, is called “Garbage in. Garbage out.”

The meta-analyses included the studies from the late 90s and early 2000s, but the positive data from those studies was swamped out by all the recent negative studies, most of which suffered from the same flaws as the study I reviewed above. This is the “Achilles’ Heel” of meta-analysis. If they include flawed studies in their analysis, their conclusions will also be flawed. What the recent studies do tell us is that omega-3s are of little additional benefit if you are already taking multiple heart medications.

Don’t Throw The Baby Out With The Bathwater

The next time you visit your doctor you are likely to be told: “The evidence is in. We know that omega-3s don’t reduce the risk of heart attack.” Now you know the truth. What we can definitively conclude is that omega-3s offer little additional benefit if you are already taking multiple heart medications. As I said before, that question may be of interest to your doctor but is probably not the question you had in mind.

Unfortunately, because of the way clinical studies of omega-3 supplementation and heart disease risk are currently conducted, we may never have a definitive answer to whether omega-3s reduce heart disease risk for those of us who aren’t taking heart medications.

Unfortunately, because of the way clinical studies of omega-3 supplementation and heart disease risk are currently conducted, we may never have a definitive answer to whether omega-3s reduce heart disease risk for those of us who aren’t taking heart medications.

However, even if there is some controversy about omega-3s and heart disease risk, there are multiple other reasons for making sure that your omega-3 status is optimum. For example:

- We know that omega-3s reduce triglycerides. This is non-controversial.

- There is excellent evidence that omega-3s improve arterial health and reduce blood pressure.

- There is good evidence that omega-3s reduce inflammation.

If they also reduce heart disease risk, consider that to be a side benefit.

The Bottom Line

A recent study has reported that that omega-3s do not reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke. However, the study suffered from multiple flaws.

- Omega-3s reduced the risk of cardiovascular deaths in the study by 18%. That never got reported by the media.

- The study was looking at subjects at relatively low risk of heart disease.

If you can’t even prove statins are effective in low risk populations, why would you expect to be able to show omega-3s are effective in low risk populations.

- The subjects had near optimum omega-3 status before the study even began.

If the subjects were already at near optimum omega-3 status, why would you expect additional omega-3 supplementation to be beneficial?

- The subjects were on 3-5 heart medications that provided many of the same benefits as omega-3s, but with side effects.

If subjects are already on 3-5 heart medications that duplicate the benefits of omega-3s, why would you expect omega-3 supplementation to be beneficial?

Two recent meta-analyses also concluded that omega-3s do not reduce the risk of heart disease. However, most of the studies in those meta-analyses suffered from the same flaws as the study I reviewed in this article. The meta-analyses are an excellent example of what computer programmers refer to as “Garbage in. Garbage out.”

The next time you visit your doctor you are likely to be told: “The evidence is in. We know that omega-3s don’t reduce the risk of heart attack.” Now you know the truth. What we can definitively conclude is that omega-3s offer little additional benefit if you are already taking multiple heart medications. That question may be of interest to your doctor, but that is probably not the question you had in mind.

Unfortunately, because of the way that clinical studies of omega-3 supplementation and heart disease risk are currently conducted, we may never have a definitive answer to whether omega-3s reduce heart disease risk for those of us who aren’t taking heart medications.

However, even if there is some controversy about omega-3s and heart disease risk, there are multiple other reasons for making sure that your omega-3 status is optimum. For example:

- We know that omega-3s reduce triglycerides. This is non-controversial.

- There is excellent evidence that omega-3s improve arterial health and reduce blood pressure.

- There is good evidence that omega-3s reduce inflammation.

If they also reduce heart disease risk, consider that to be a side benefit.

For more details, read the article above.

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This information is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease.