Where Can Seniors Find The Protein And Leucine They Need?

Author: Dr. Stephen Chaney

Most Americans lose lean muscle mass as they age, a physiological process called sarcopenia. There are three factors that influence the rate at which we lose muscle mass as we age:

Most Americans lose lean muscle mass as they age, a physiological process called sarcopenia. There are three factors that influence the rate at which we lose muscle mass as we age:

- Our physiology changes. Our bodies break down our protein stores more rapidly and we have a harder time utilizing the protein in our diet to replenish those protein stores.

- We become less active. In some cases, this reflects physical disabilities, but all too often it is because we are not giving weight-bearing exercises the proper priority in our busy lives.

- Our diets have become inadequate. A major driver of this phenomenon is loss of appetite which results in decreased caloric intake. However, physical disability, isolation, and insufficient income also contribute.

Some of you may be saying “So what? I wasn’t planning on being a champion weightlifter in my golden years.” The “So what” is that loss of muscle mass leads to reduced mobility, a tendency to fall (which often leads to debilitating bone fractures) and a lower metabolic rate – which leads to obesity and all the illnesses that go along with obesity.

Fortunately, sarcopenia is not an inevitable consequence of aging. There are things that we can do to prevent it. The most important thing that we can do to prevent muscle loss as we age is to exercise – and I’m talking about resistance (weight) training, not just aerobic exercise.

But we also need to optimize our protein intake and our leucine intake. Protein is important because our muscle fibers are made of protein.

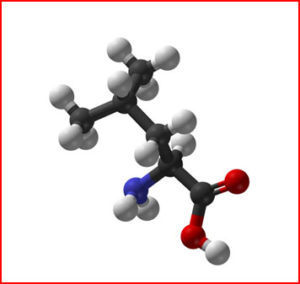

Leucine is an essential amino acid. It is important because it stimulates the muscle’s ability to make new protein. Leucine and insulin act synergistically to stimulate muscle protein synthesis after exercise.

In a previous issue of “Health Tips From the Professor” I shared studies showing that the amount of protein and leucine we need to prevent muscle loss increases as we get older. The study (ME Lixandrao et al, Nutrients, Volume 13, Issue 10, 10.3390/nu13103536) I am reviewing today is an update on the leucine needs for seniors.

How Was This Study Done?

The investigators recruited 67 healthy, elderly, overweight adults (34 men and 33 women; average age = 69.7; average BMI = 26.4) in Basel, Switzerland for the study. The participants selected for the study were not engaged in any kind of regular resistance or aerobic training in the previous 6 months.

The investigators recruited 67 healthy, elderly, overweight adults (34 men and 33 women; average age = 69.7; average BMI = 26.4) in Basel, Switzerland for the study. The participants selected for the study were not engaged in any kind of regular resistance or aerobic training in the previous 6 months.

Participants were asked to fill in three 24-hour dietary recalls (2 on non-consecutive weekdays and one on a weekend day). A trained nutritionist gave instructions on how to perform the dietary recalls. After the dietary recalls were completed, the nutritionists used pictures of foods included in each participant’s diet recall to confirm the accuracy of their portion size estimates. This diet information was used to calculate habitual daily protein and leucine intake.

The investigators used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to measure quadriceps cross-sectional area – a measure of muscle mass. They also used performance on a leg extension machine to measure unilateral maximum dynamic muscle strength – a measure of muscle strength.

The study correlated leucine intake with both muscle mass and muscle strength. The data were corrected for sex, age, and total protein intake normalized to body weight.

How Much Leucine Do Seniors Need?

There was a biphasic correlation between leucine intake and both muscle mass and muscle strength in this population.

There was a biphasic correlation between leucine intake and both muscle mass and muscle strength in this population.

- There was a positive association between leucine intake and muscle mass up to 7.6 gm/day. After that a plateau was reached. Additional leucine had no effect on muscle mass.

- There was a positive association between leucine intake and muscle strength up to 8.0 gm/day. After that a plateau was reached. Additional leucine had no effect on muscle strength.

- These associations held true even after correcting for total protein intake. This is an important control because none of these participants were taking a leucine supplement, so those consuming more leucine were also consuming more protein.

The authors concluded, “We demonstrated that total daily leucine intake is associated with muscle mass and strength in healthy older individuals, and this association remains after correcting for multiple factors, including overall protein intake. Furthermore, our…analysis revealed…a potential threshold for habitual leucine intake, which may guide future research on the effect of chronic leucine intake in age-related muscle loss [sarcopenia].

Randomized control trials should test the utility of additional leucine to counteract frailty in the elderly.”

What Does This Study Mean For You?

Let me start by saying that leucine is not a “magic bullet” that will prevent sarcopenia (age-related loss of muscle mass) by itself. Three things are essential for preventing sarcopenia:

Let me start by saying that leucine is not a “magic bullet” that will prevent sarcopenia (age-related loss of muscle mass) by itself. Three things are essential for preventing sarcopenia:

- Resistance (weight bearing) exercise. You should aim for at least 3 days/week of moderate intensity weight bearing exercise a week.

If you have physical limitations, consult with your health professional before beginning an exercise program. And if you have not done weight bearing exercise before, it is best to start with instruction from a personal trainer to be sure you are using appropriate weights and appropriate form.

[Note: The participants in this study had not done weight bearing exercise for 6 months prior to the study and did not exercise during the study.]

- Adequate protein. I have discussed this in a previous issue of “Health Tips From the Professor”. If you are in your 30’s, 15-20 grams of protein per meal will do. But if you are in your 60’s and above, it’s better to aim for 25-30 grams of protein per meal.

[Note: On average the men in this study were consuming 87 grams of protein per day. That’s 29 grams per meal. The women in this study averaged 67 grams of protein per day or 22 grams per meal. So, most of the participants in this study were consuming adequate protein.]

- Adequate leucine. This study showed that the benefits of leucine plateaued at around 7.6-8.0 grams per day or 2.5 to 2.7 grams per meal for non-exercising adults in their 60’s and 70’s.

This is in close agreement with studies showing that 25-30 grams of protein and 2.7 grams of leucine were optimal for seniors in this age range following weight bearing exercise.

[Note: This study only determined the optimal intake of leucine. Remember for maximal effectiveness at reducing age-related muscle mass (sarcopenia) you need optimal protein, optimal leucine, and an optimal resistance (weight bearing) exercise program.]

Where Can Seniors Find The Protein And Leucine They Need?

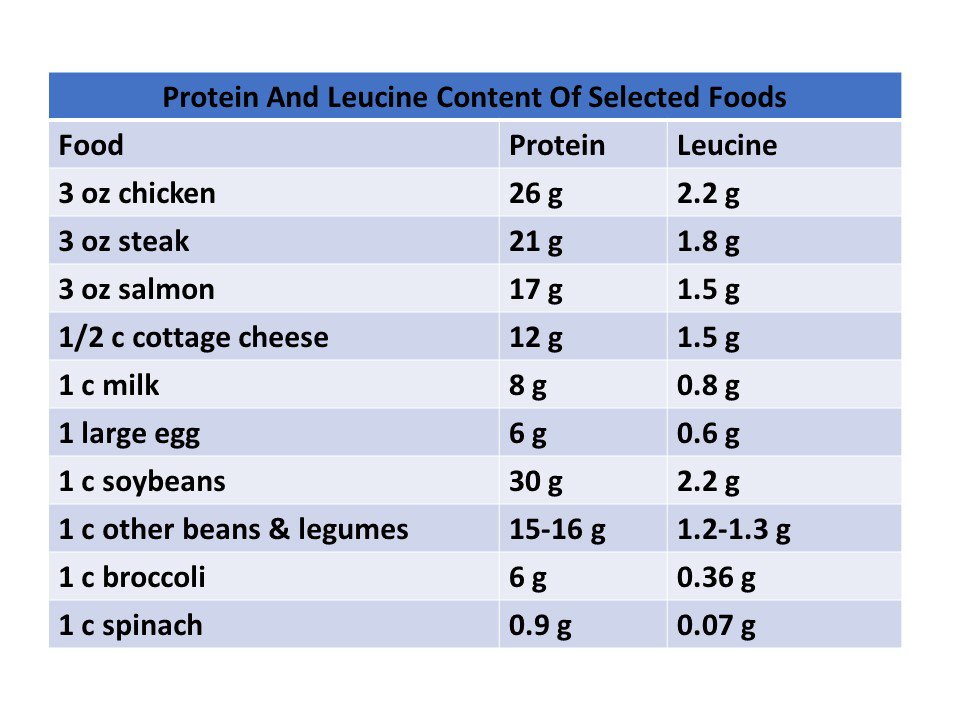

For most Americans this is not too difficult as the table above shows. If you look at single foods, chicken and soybeans are the best sources of both protein and leucine. Other meats and other beans & legumes are also good choices.

For most Americans this is not too difficult as the table above shows. If you look at single foods, chicken and soybeans are the best sources of both protein and leucine. Other meats and other beans & legumes are also good choices.

I included things like eggs, dairy foods, broccoli, and spinach as a reminder that you don’t need to get all your protein and leucine from a single food source. Other whole foods included in your meal can contribute to your protein and leucine totals.

This table also shows that you don’t need to be a carnivore to get the protein and leucine you need. However, if you avoid most meats or are a pure vegan, you will need to plan your diet a bit more carefully.

Finally, if you are looking to optimize your workouts with an after-workout plant-based protein shake, soy protein would be your best choice. If you chose plant protein, you should look for high-quality protein shakes with added leucine to make sure you meet both your protein and leucine goals.

The Bottom Line

Most Americans lose lean muscle mass as we age, a physiological process called sarcopenia. This loss of muscle mass leads to reduced mobility, a tendency to fall (which often leads to debilitating bone fractures) and a lower metabolic rate – which leads to obesity and all the illnesses that go along with obesity.

Fortunately, sarcopenia is not an inevitable consequence of aging. There are 3 things we can do to prevent it.

- Exercise – and I’m talking about resistance (weight) training, not just aerobic exercise. This is the most important thing that we can do to prevent muscle loss as we age.

- Optimize our protein intake.

- Optimize our leucine intake.

Previous studies have determined the optimal protein intake for preventing sarcopenia. The study I describe above determined the optimal leucine intake.

For more details about the study and what it means for you, read the article above.

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This information is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.

______________________________________________________________________________

My posts and “Health Tips From the Professor” articles carefully avoid claims about any brand of supplement or manufacturer of supplements. However, I am often asked by representatives of supplement companies if they can share them with their customers.

My answer is, “Yes, as long as you share only the article without any additions or alterations. In particular, you should avoid adding any mention of your company or your company’s products. If you were to do that, you could be making what the FTC and FDA consider a “misleading health claim” that could result in legal action against you and the company you represent.

For more detail about FTC regulations for health claims, see this link.

https://www.ftc.gov/business-guidance/resources/health-products-compliance-guidance

______________________________________________________________________

About The Author

Dr. Chaney has a BS in Chemistry from Duke University and a PhD in Biochemistry from UCLA. He is Professor Emeritus from the University of North Carolina where he taught biochemistry and nutrition to medical and dental students for 40 years. Dr. Chaney won numerous teaching awards at UNC, including the Academy of Educators “Excellence in Teaching Lifetime Achievement Award”. Dr Chaney also ran an active cancer research program at UNC and published over 100 scientific articles and reviews in peer-reviewed scientific journals. In addition, he authored two chapters on nutrition in one of the leading biochemistry text books for medical students.

Since retiring from the University of North Carolina, he has been writing a weekly health blog called “Health Tips From the Professor”. He has also written two best-selling books, “Slaying the Food Myths” and “Slaying the Supplement Myths”. And most recently he has created an online lifestyle change course, “Create Your Personal Health Zone”. For more information visit https://chaneyhealth.com.

For the past 45 years Dr. Chaney and his wife Suzanne have been helping people improve their health holistically through a combination of good diet, exercise, weight control and appropriate supplementation.