How Should You Interpret This Study?

Author: Dr. Stephen Chaney

February is Heart Health month. So, it is fitting that we ask, “What is the status of heart health in this country?” The American Heart Association just published an update of heart health statistics through 2019 (CW Tsao et al, Circulation, 145: e153-e639, 2022). And the statistics aren’t encouraging. [Note: The American Heart Association only reported statistics through 2019 because the COVID-19 pandemic significantly skewed the statistics in 2020 and 2021].

February is Heart Health month. So, it is fitting that we ask, “What is the status of heart health in this country?” The American Heart Association just published an update of heart health statistics through 2019 (CW Tsao et al, Circulation, 145: e153-e639, 2022). And the statistics aren’t encouraging. [Note: The American Heart Association only reported statistics through 2019 because the COVID-19 pandemic significantly skewed the statistics in 2020 and 2021].

The Good News is that between 2009 and 2019:

- All heart disease deaths have decreased by 25%.

- Heart attack deaths have decreased by 6.6%.

- Stroke deaths have decreased by 6%.

The Bad News is that:

- Heart disease is still the leading cause of death in this country.

- Someone dies from a heart attack every 40 seconds.

- Someone dies from a stroke every 3 minutes.

Diet, exercise, and weight control play a major role in reducing the risk of heart disease. Best of all, they have no side effects. They represent a risk-free approach that each of us can control.

But is there something else? Could supplements play a role? Are supplements hype or hope for a healthy heart?

All the Dr. Strangeloves in the nutrition space have their favorite heart health supplements. They claim their supplements will single-handedly abolish heart disease (and help you leap tall buildings in a single bound).

On the other hand, many doctors will tell you these supplements are a waste of money. They don’t work. They just drain your wallet.

It’s so confusing. Who should you believe? Fortunately, a recent study (P An et al, Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 80: 2269-2285, 2022) has separated the hype from the hope and tells us which “heart-healthy” supplements work, and which don’t.

How Was This Study Done?

This was a major clinical study carried out by researchers from the China Agricultural University and Brown University in the US. It was a meta-analysis, which means it combined the data from many published clinical trials.

This was a major clinical study carried out by researchers from the China Agricultural University and Brown University in the US. It was a meta-analysis, which means it combined the data from many published clinical trials.

The investigators searched three major databases of clinical trials to identify:

- 884 randomized, placebo-controlled clinical studies…

- Of 27 types of micronutrients…

- With a total of 883,627 patients…

- Looking at the effectiveness of micronutrient supplementation lasting an average of 3 years on either…

-

- Cardiovascular risk factors like blood pressure, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides…or…

-

- Cardiovascular outcomes such as coronary heart disease (CHD), heart attacks, strokes, and deaths due to cardiovascular disease (CVD) and all causes.

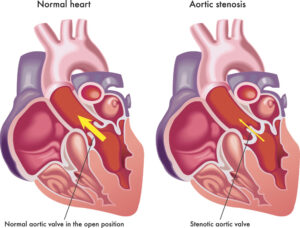

[Note: Coronary heart disease (CHD) refers to build up of plaque in the coronary arteries (the arteries leading to the heart). It is often referred to as heart disease and can lead to heart attacks (myocardial infarction). Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a more inclusive term that includes coronary heart disease, stroke, congenital heart defects, and peripheral artery disease.]

The investigators also included an analysis of the quality of the data in each of the clinical studies and rated the evidence of each of their findings as high quality, moderate quality, or low quality.

Which Supplements Are Good For Your Heart?

The top 3 heart-healthy supplements in this study were:

- Increased HDL cholesterol and decreased triglycerides, both favorable risk factors for heart health.

- Deceased risk of heart attacks by 15%, all CHD events by 14%, and CVD deaths by 7% (see definitions of CHD and CVD above).

- The median dose of omega-3 fatty acids in these studies was 1.8 g/day.

- The evidence was moderate quality for all these findings.

Folic Acid:

- Decreased LDL cholesterol (moderate quality evidence) and decreased blood pressure and total cholesterol (low quality evidence).

- Decreased stroke risk by 16% (moderate quality evidence).

Coenzyme Q10:

- Decreased triglycerides (high quality evidence) and reduced blood pressure (low quality evidence).

- Decreased the risk of all-cause mortality by 32% (moderate quality evidence).

- These studies were performed with patients diagnosed with heart failure. Coenzyme Q10 is often recommended for these patients, so the studies were likely performed to test the efficacy of this treatment.

There were three micronutrients (vitamin C, vitamin E, and vitamin D) that did not appear to affect heart disease outcomes.

Finally, as reported in previous studies, β-carotene increased the risk of stroke, CVD mortality, and all-cause mortality.

In terms of the question I asked at the beginning of this article, this study concluded that:

- Omega-3, folic acid, and coenzyme Q10 supplements represent hope for a healthy heart.

- Vitamin C, vitamin E, and vitamin D supplements represent hype for a healthy heart.

- β-carotene supplements represent danger for a healthy heart.

But these conclusions just scratch the surface. To put them into perspective we need to dig a bit deeper.

How Should You Interpret This Study?

In evaluating the significance of these findings there are two things to keep in mind.

In evaluating the significance of these findings there are two things to keep in mind.

#1: This study is a meta-analysis and meta-analyses have both strengths and weaknesses.

The strength of meta-analyses is that by combining multiple clinical studies they can end up with a database containing 100s of thousands of subjects. This allows them to do two things:

- It allows the meta-analysis to detect statistically significant effects that might be too small to detect in an individual study.

- It allows the meta-analysis to detect the average effect of all the clinical studies it includes.

The weakness of meta-analyses is that the design of individual studies included in the analysis varies greatly. The individual studies vary in things like dose, duration, type of subjects included in the study, and much more.

This is why this study rated most of their conclusions as backed by moderate- or low-quality evidence. [Note: The fact that the authors evaluated the quality of evidence is a strength of this study. Most meta-analyses just report their conclusions without telling you how strong the evidence behind those conclusions is.]

#2: Most clinical studies of supplements (including those included in this meta-analysis) have two significant weaknesses.

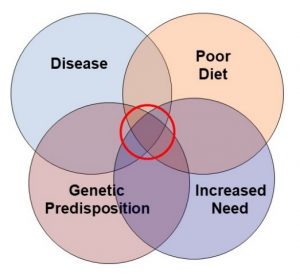

- Most studies do not measure the nutritional status of their subjects prior to adding the supplement. If their nutritional status for a particular nutrient was already optimal, there is no reason to expect more of that nutrient to provide any benefit.

- Most studies measure the effect of a supplement on a cross-section of the population without asking who would be most likely to benefit.

You would almost never design a clinical study that way if you were evaluating the effectiveness of a potential drug. So, why would you design clinical studies of supplements that way?

With these considerations in mind, let me provide some perspective on the conclusions of this study.

Coenzyme Q10:

This meta-analysis found that coenzyme Q10 significantly reduced all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure. This is consistent with multiple clinical studies and a recent Cochrane Collaboration review.

Does coenzyme Q10 have any heart health benefits for people without congestive heart failure? There is no direct  evidence that it does, but let me offer an analogy with statin drugs.

evidence that it does, but let me offer an analogy with statin drugs.

Statin drugs are very effective at reducing heart attacks in high-risk patients. But they have no detectable effect on heart attacks in low-risk patients. However, this has not stopped the medical profession from recommending statins for millions of low-risk patients. The rationale is that if they are so clearly beneficial in high-risk patients, they are “probably” beneficial in low-risk patients.

I would argue a similar rationale should apply to supplements like coenzyme Q10.

Omega-3s:

This study found that omega-3 reduced both heart attacks and the risk of dying from heart disease. Most previous meta-analyses of omega-3s and heart disease have come to the same conclusion. However, some meta-analyses have failed to find any heart health benefits of omega-3s. Unfortunately, this has allowed both proponents and opponents of omega-3 use for heart health to quote studies supporting their viewpoint.

However, there is one meta-analysis that stands out from all the others. A group of 17 scientists from across the globe collaborated in developing a “best practices” experimental design protocol for assessing the effect of omega-3 supplementation on heart health. They conducted their clinical studies independently, and when their data (from 42,000 subjects) were pooled, the results showed that omega-3 supplementation decreased:

- Premature death from all causes by 16%.

- Premature death from heart disease by 19%.

- Premature death from cancer by 15%.

- Premature death from causes other than heart disease and cancer by 18%.

This study eliminates the limitations of previous meta-analyses. That makes it much stronger than the other meta-analyses. And these results are consistent with the current meta-analysis.

Omega-3s have long been recognized as essential nutrients. It is past time to set Daily Value (DV) recommendations for omega-3s. Based on the recommendations of other experts in the field, I think the DV should be set at 500-1,000 mg/day. I take more than that, but this would represent a good minimum recommendation for heart health.

As with omega-3s, this meta-analysis reported a positive effect of folic acid on heart health. But many other studies have come up empty. Why is that?

It may be because, between food fortification and multivitamin use, many Americans already have sufficient blood levels of folic acid. For example, one study reported that 70% of the subjects in their study had optimal levels of folates in their blood. And that study also reported:

- Subjects with adequate levels of folates in their blood received no additional benefit from folic acid supplementation.

- However, for subjects with inadequate blood folate levels, folic acid supplementation decreased their risk of heart disease by ~15%.

We see this pattern over and over in supplement studies. Supplement opponents interpret these studies as showing that supplements are worthless. But a better interpretation is that supplements benefit those who need them.

The problem is that we don’t know our blood levels of essential nutrients. We don’t know which nutrients we need, and which we don’t. That’s why I like to think of supplements as “insurance” against the effects of an imperfect diet.

Vitamins E and D:

The situation with vitamins E and D is similar. This meta-analysis found no heart health benefit of either vitamin E or D. That is because the clinical studies included in the meta-analysis asked whether vitamin E or vitamin D improved heart health for everyone in the study.

Previous studies focusing on patients with low blood levels of these nutrients and/or at high risk of heart disease have shown some benefits of both vitamins at reducing heart disease risk.

So, for folic acid, vitamin E, and vitamin D (and possibly vitamin C) the take-home message should be:

- Ignore all the Dr. Strangeloves telling you that these vitamins are “magic bullets” that will dramatically reduce your risk of heart disease.

- Ignore the naysayers who tell you they are worthless.

- Use supplementation wisely to make sure you have the recommended intake of these and other essential nutrients.

This meta-analysis reported that β-carotene increased the risk of heart disease. This is not a new finding. Multiple previous studies have come to the same conclusion.

And we know why this is. There are many naturally occurring carotenoids, and they each have unique heart health benefits. A high dose β-carotene supplement interferes with the absorption of the other carotenoids. You are creating a deficiency of other heart-healthy carotenoids.

If you are not getting lots of colorful fruits and vegetables from your diet, my recommendation is to choose a supplement with all the naturally occurring carotenoids in balance – not a pure β-carotene supplement.

The Bottom Line

The Dr. Strangeloves in the nutrition space all have their favorite heart health supplements. They claim their supplements will single-handedly abolish heart disease (and help you leap tall buildings in a single bound).

On the other hand, many doctors will tell you these supplements are a waste of money. They don’t work. They just drain your wallet.

It’s so confusing. Who should you believe? Fortunately, a recent study has separated the hype from the hope and tells us which “heart-healthy” supplements work, and which don’t.

This study was a meta-analysis of 884 clinical studies with 883,627 participants. It reported:

- Omega-3 supplementation deceased risk of heart attacks by 15% and all cardiovascular deaths by 7%.

- Folic acid supplementation decreased stroke risk by 16%.

- Coenzyme Q10 supplementation decreased the risk of all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure by 32%.

- Vitamin C, vitamin E, vitamin D did not appear to affect heart disease outcomes.

- β-carotene increased the risk of stroke, CVD mortality, and all-cause mortality.

For more details on this study and what it means for you, read the article above.

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This information is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.