The “Secret” About Clinical Studies Nobody Is Telling You

Author: Dr. Stephen Chaney

It is so confusing. You get lots of advice in today’s world.

It is so confusing. You get lots of advice in today’s world.

- Your friend shares a new diet they read about and tells you how well it worked for her.

- Your trainer puts you on a diet his sports guru recommended.

- You read Dr. Strangelove’s health blog and decide you need to throw out all the foods in your refrigerator.

- Your doctor tells you what you should eat and whether you should take supplements.

- You decide to follow the recommendations of the American Heart Association or American Diabetes Association because they are the experts.

The problem is you are told all this advice is based on clinical studies – AND – most of the advice is conflicting. You don’t know who to believe, and, even worse, you are starting to wonder whether you can believe clinical studies.

I have covered the source of much of this confusion in my two books “Slaying The Food Myths” and “Slaying The Supplement Myths.” The Cliff Notes summary from these books is:

- The placebo effect approaches 50% for things like feeling good, energy and mood.

- Reputable scientists ignore testimonials and look for clinical proof.

- What works for your friend or trainer may not work for you.

- Any extreme diet that eliminates foods and food groups from your diet will cause short-term weight loss and improvements in health parameters like cholesterol, blood sugar, and blood pressure.

- Reputable scientists look for studies documenting the long-term health outcomes of those diets. Some diets that look healthy short-term are unhealthy long-term.

- Advocates of these fad diets emphasize short-term successes of their favorite diet and don’t even look for studies on long-term health outcomes.

Every clinical study has its flaws.

Reputable scientists recognize this and don’t base their recommendations on individual studies. Instead, they base their recommendation on the preponderance of evidence from multiple studies.

Reputable scientists recognize this and don’t base their recommendations on individual studies. Instead, they base their recommendation on the preponderance of evidence from multiple studies.- Strangelove and other bloggers don’t understand that. They select studies that support their viewpoint and ignore the rest.

- Some clinical studies are better than others. In fact, some really bad clinical studies get published.

- Reputable scientists know how to distinguish between good studies and bad studies. They ignore bad studies and base their recommendations on good studies.

- Strangelove, other bloggers, and the news media aren’t scientists. They don’t know how to distinguish between good and bad studies. They simply report the studies that support their viewpoint.

- Strangelove, other bloggers, and the new media prefer audience over accuracy. They measure success by the number of readers rather than the accuracy of their articles.

- “Man bites dog” stories gather the most readers. Dr. Strangelove and the media focus on studies that challenge the advice you have been getting from the health and nutrition establishment. The studies may not be accurate, but they attract a lot of readers.

- Responsible scientists will give you the boring truth, even if it doesn’t attract many readers.

In my books I help you navigate through the world of conflicting clinical studies, so you can base your decisions on the very best clinical studies. However, there is one more “secret” you need to know. It is one that every scientist knows, but the public almost never hears about.

However, before I tell you the secret, let me set up this discussion by talking about glycemic index and use one food, the lowly banana, as an example.

Glycemic Index – How Sweet It Is

If you are a diabetic or are following one of the many low-carb diets, you probably know all about glycemic index. You probably have a glycemic index list in your kitchen or on your phone. You probably consult that list often to determine which foods you can eat and which you can’t. (If you aren’t familiar with the term, it is simply a measure of how big a blood sugar increase each food causes).

If you are a diabetic or are following one of the many low-carb diets, you probably know all about glycemic index. You probably have a glycemic index list in your kitchen or on your phone. You probably consult that list often to determine which foods you can eat and which you can’t. (If you aren’t familiar with the term, it is simply a measure of how big a blood sugar increase each food causes).

What if I were to tell you the glycemic index list you are relying on may not apply to you?

Then there is the lowly banana. You have probably heard from your trainer or favorite nutrition blog that you should avoid bananas because they are too high in sugar. However, if you were to consult a nutrition expert, they would tell you that bananas are a great choice. Bananas are nutrient powerhouses. In addition, a ripe banana has a glycemic index of 51 and anything under 55 is considered low-glycemic.

What if I were to tell you that the advice about bananas that both your trainer and nutrition experts give you is correct for some people? You just need to find out which advice applies to you.

The Secret About Clinical Studies Nobody Is Telling You

Now, you are ready to learn the secret. It is this: Clinical studies are based on averages, and none of us are average. Because of that, even the very best clinical study results may not apply to you.

Now, you are ready to learn the secret. It is this: Clinical studies are based on averages, and none of us are average. Because of that, even the very best clinical study results may not apply to you.

In a way, this reminds me of “The Wizard Of Oz.” You remember the story. If you were sitting in front of the curtain, the wizard was impressive. He was all powerful. He was making learned pronouncements about the way things should be. But, behind the curtain, the reality was quite different.

The authors of most clinical studies and most nutrition gurus make learned pronouncements about the life changes you should make based on the results of their study. They seldom let you peak behind the curtain to see how much the results vary from one individual to the next.

One exception is a recent study that reported individual variation in blood sugar responses to various foods. There are lots of examples from that study I could share with you, but I will use bananas versus sugar cookies as an example.

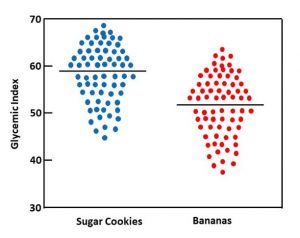

When they reported average values, bananas had a glycemic index of 51 and sugar cookies had a glycemic index of around 59. Both of those values are very close to what you find in most glycemic index lists.

The glycemic index of a banana is only 13% less than the glycemic index of sugar cookies. However, since the cut-off between high and low glycemic indices is 55, bananas are classified as low-glycemic and sugar cookies are classified as high-glycemic. According to conventional wisdom, bananas are good for you and sugar cookies are bad for you. But, what about individual variation? Does that wisdom really apply to you?

Based on the range of blood-sugar responses reported in the paper, I have created the scatter plot on the left to help you visualize the range of individual responses. The horizontal line represents the average glycemic index for sugar cookies and bananas. The dots represent the glycemic response of individuals in the study. For some people in the study the glycemic response to bananas was greater than the average glycemic response to sugar cookies. For other individuals the glycemic response to sugar cookies was less than the average glycemic response to bananas.

Based on the range of blood-sugar responses reported in the paper, I have created the scatter plot on the left to help you visualize the range of individual responses. The horizontal line represents the average glycemic index for sugar cookies and bananas. The dots represent the glycemic response of individuals in the study. For some people in the study the glycemic response to bananas was greater than the average glycemic response to sugar cookies. For other individuals the glycemic response to sugar cookies was less than the average glycemic response to bananas.

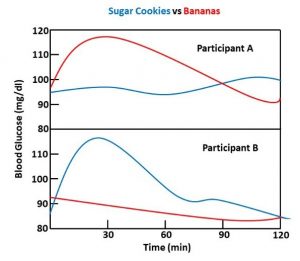

You can see the extent of individual variability even more clearly in the figure on the right, which was reproduced from one of the figures in the paper. The authors reported that for some individuals, bananas caused no increase in blood sugar while sugar cookies caused a big spike in blood sugar (the response most people would expect). However, for other individuals, sugar cookies caused no increase in blood sugar while bananas caused a big spike in blood sugar.

Now you understand why I told you the glycemic list you are relying on may not apply to you. You also understand why I said the advice you have been given about bananas might not apply to you.

Now you understand why I told you the glycemic list you are relying on may not apply to you. You also understand why I said the advice you have been given about bananas might not apply to you.

Lest you think this just applies to bananas, the same study reported that individual blood sugar responses varied by:

- 4-fold for sugar-sweetened soft drinks, grapes, and apples.

- 5-fold for rice.

- 6-fold for bread and potatoes.

- 7-fold for ice cream and dates.

Can You Believe Clinical Studies?

I used glycemic index as an example. The same principle is true for almost any clinical study.

I used glycemic index as an example. The same principle is true for almost any clinical study.

Let’s consider clinical studies looking at the effect of diet on health outcomes such as heart disease.

- The headlines may say that a particular diet significantly decreases your risk of heart disease.

- When you read the paper behind the headlines, you discover that the diet decreases heart disease by 15%. That result may be statistically significant, but it is hardly life changing.

- If you could peak behind the curtain you might discover that the diet cut heart disease risk in half for some individuals and had no effect on heart disease risk for others.

Clinical studies looking at weight loss are another example.

- You might be told “Clinical studies show people who follow diet X lose 12 pounds in 6 weeks”.

- That’s an average value. If you could peak behind the curtain, you would discover that nobody lost exactly 12 pounds. Some lost more. Some lost less. Some may have actually gained weight.

I am not saying that well-designed clinical studies are useless. They are a good foundation for general nutrition guidelines. What I am saying is that not every nutritional guideline applies to you.

What Does This Study Mean For You?

Some of you may be saying: “What does this mean for me?” When you carry the concept of individual variability through to its ultimate conclusion, the bottom line message is:

Some of you may be saying: “What does this mean for me?” When you carry the concept of individual variability through to its ultimate conclusion, the bottom line message is:

- Conclusions from clinical trial results are based on averages – none of us are average.

- Daily Values (DV) are based on averages – none of us are average.

- Nutritional recommendations for optimal health are based on averages – none of us are average.

- The identified risk factors for developing diseases are based on averages – none of us are average.

- Glycemic index lists are based on averages. None of us are average.

That means lots of the advice you may be getting about your risk of developing disease X, the best diet to prevent disease X, the best foods to keep your blood sugar under control, or the role of supplementation in preventing disease X may be generally true – but it might not be true for you.

So, my advice is not to blindly accept the advice of others about what is right for your body. Just because some health guru recommends it, doesn’t mean it is right for you. Just because it worked for your buddy, doesn’t mean it will work for you. Learn to listen to your body. Learn what foods work best for you. Learn what exercises just feel right for you. Learn what supplementation does for you.

Don’t ignore your doctor’s recommendations, but don’t be afraid to take on some of the responsibility for your own health. You are a unique individual, and nobody else knows what it is like to be you.

Final Thought: Glycemic Index Versus Glycemic Load

Since I used glycemic index as an example in this discussion, I feel obligated to discuss the difference between glycemic index and glycemic load. Glycemic index is based on the blood sugar response to 50 gm of carbohydrate in various foods. Glycemic load is based on the blood sugar response to a serving of that food. In some cases, that’s a big difference.

Glycemic index can sometimes be deceiving. Let me give you two examples. Carrots and watermelon are often found on lists of high glycemic foods. If that sounds a bit weird to you, it is.

One serving (one medium carrot) of carrots has 6 grams of carbohydrate (of which, only 2.9 grams is sugar). To get 50 grams of carbohydrate, you would need to eat 8 carrots. Watermelon is, not surprisingly, mostly water. One serving (a 1-inch thick sliced wedge or one cup) of watermelon contains 11 grams of carbohydrate (of which, 9 grams of sugar). To get 50 grams of sugar, you would need to eat 4.5 cups of watermelon. For both carrots and watermelon, their glycemic load is a more accurate measure of their effect on your blood sugar than is their glycemic index.

Leaving individual variation out of consideration, here is a simple guide for choosing low-glycemic foods if you are trying to control your blood sugar levels.

- Foods with a low glycemic index are generally a good choice.

- Many foods with a high glycemic index also have a high glycemic load.

- If you are uncertain about some foods on the high glycemic index list, also check their glycemic load.

The Bottom Line

Clinical studies are the bedrock on which we build recommendations for diet, exercise, and supplementation. In the article above I discuss how to distinguish between good and bad clinical studies. I also discuss how individual variability influences the interpretation of clinical studies.

For more details read the article above.

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This information is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease.