Why The Recent Headlines May Be Misleading

Author: Dr. Stephen Chaney

Does calcium help prevent bone fractures? Osteoporosis is a debilitating and potentially deadly disease associated with aging. It affects 54 million Americans. It can cause debilitating back pain and bone fractures. 50% of women and 25% of men over 50 will break a bone due to osteoporosis. Hip fractures in the elderly due to osteoporosis are often a death sentence.

Does calcium help prevent bone fractures? Osteoporosis is a debilitating and potentially deadly disease associated with aging. It affects 54 million Americans. It can cause debilitating back pain and bone fractures. 50% of women and 25% of men over 50 will break a bone due to osteoporosis. Hip fractures in the elderly due to osteoporosis are often a death sentence.

For that reason, the RDA for calcium has been set at 1,000 to 1,200 mg/day to reduce the risk of osteoporosis, and calcium supplements are often recommended to reach that target.However, recent headlines are proclaiming that calcium supplements do not actually prevent bone fractures and might increase your risk of a heart attack. Are the RDA recommendations wrong? Should you throw out your calcium supplements?

In this article I will review the article behind the study and help you put it into perspective. After all, you don’t really want to know whether calcium supplementation is beneficial for the average adult. You want to know whether it will be beneficial for you.

Let me start by putting the heart attack myth to rest. I have covered this in detail in a previous “Health Tips From The Professor” article, Calcium Supplements Increase Heart Attack Risk . If you don’t want to go to the trouble of reading my previous article, the short version is that:

- Most of the studies suggesting an increased risk of heart attacks are flawed.

- A very large study (74,000 women followed for 24 years) has shown fairly convincingly that calcium supplements do not increase heart attack risk. If anything, they decrease heart attack risk.

Unfortunately, like most other nutrition myths, this one is still being repeated – even after it has been refuted by subsequent studies.

Bone Metabolism and Osteoporosis

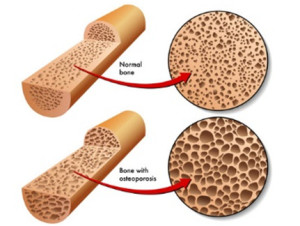

Before you can truly understand osteoporosis and how to prevent it, you need to know a bit about bone metabolism. We tend to think of our bones as solid and unchanging, much like the steel girders in an office building. Nothing could be further from the truth. Our bones are dynamic organs that are in a constant change throughout our lives.

Before you can truly understand osteoporosis and how to prevent it, you need to know a bit about bone metabolism. We tend to think of our bones as solid and unchanging, much like the steel girders in an office building. Nothing could be further from the truth. Our bones are dynamic organs that are in a constant change throughout our lives.

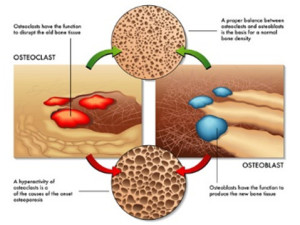

Cells called osteoclasts and osteoblasts constantly break down old bone (a process called resorption) and replace it with new bone (a process called accretion). Without this constant renewal process our bones would quickly become old and brittle (I’ll discuss more about this next week when I talk about the side effects of drugs commonly used to increase bone density).

When we are young the bone building process exceeds bone resorption and our bones grow in size and in density. During most of our adult years, bone resorption and accretion are in balance so our bone density stays constant. However, as we age bone the bone building process (accretion) slows down and we start to lose bone density. Eventually our bones look like Swiss cheese and break very easily. This is called osteoporosis.

We should also think of our bones as calcium reservoirs. We need calcium in our bloodstream 24 hours a day for our muscles, brain, and nerves to function properly, but we only get calcium in our diet at discrete intervals. Consequently, when we eat our body tries to store as much calcium as possible in our bones. Between meals, we break down bone material so that we can release the calcium into our bloodstream that our muscle, brain & nerves need to function.

If we lead a “bone healthy” lifestyle, all of this works perfectly. We build strong bones during our growing years, maintain healthy bones during our adult years, and only lose bone density slowly as we age – maybe never experiencing osteoporosis. We always accumulate enough calcium in our bones during meals to provide for the rest of our body between meals.

What is a “bone healthy” lifestyle, you might ask. Because calcium is a major component of bone, the medical and nutrition communities have long focused on calcium as a “magic bullet” that can assure bone health. Once the importance of vitamin D was understood, it was added to the equation. For years we have been told that if we just get enough calcium and vitamin D in our diets, we would build strong bones when we were young, maintain bone density most of our adult years, and lose bone density as slowly as possible as we age.It is this paradigm that the current study challenges.

Do Calcium Supplements Prevent Bone Fractures?

Let’s start by looking at the study behind the headlines (Tai et al, British Medical Journal, BMJ/2015; 351:h4183 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4183). This was a meta-analysis that included 15 studies (1533 participants) looking at dietary sources of calcium and 51 studies (12,257 participants) looking at calcium supplementation in women.

Let’s start by looking at the study behind the headlines (Tai et al, British Medical Journal, BMJ/2015; 351:h4183 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4183). This was a meta-analysis that included 15 studies (1533 participants) looking at dietary sources of calcium and 51 studies (12,257 participants) looking at calcium supplementation in women.

The results of the meta-analysis were thought provoking, but do not exactly support the headlines you have been reading. For example:

The headlines say “Calcium Supplements Do Not Prevent Broken Bones”.

- This study did not actually look at calcium supplementation and the risk of bone fractures. That was a previous study (Boland et al, BMJ 2015, 351:h4580) by the same authors.

- This study showed that calcium supplementation increased bone density by 0.7-1.8%, which the authors concluded was sufficient to reduce fracture risk by about 5-10%. That’s a disappointingly small effect, but it is not zero – as the headlines suggested.

The headlines say “It’s better to get your calcium from food than from supplements”.

- This study showed that it did not matter whether the calcium came from food or from supplements. The increase in bone density was identical.

Garbage-In, Garbage-Out

Meta-analyses such as this one can be very strong, but they can also suffer from the “garbage-in, garbage-out” phenomenon. In short, if most of the studies that went into the meta-analysis were poorly designed, the conclusions of the meta-analysis will be unreliable.

Meta-analyses such as this one can be very strong, but they can also suffer from the “garbage-in, garbage-out” phenomenon. In short, if most of the studies that went into the meta-analysis were poorly designed, the conclusions of the meta-analysis will be unreliable.

The problem is that many of the individual studies were conducted 10, 20, 30 or 40 years ago when our knowledge of bone metabolism was incomplete.

- Thirty or 40 years ago it was “state of the art” to just use a calcium supplement. Then we learned that adequate vitamin D was essential for efficient calcium utilization.

- Most of the studies included in this meta-analysis looked at calcium supplementation without vitamin D. Only 13 of the studies (25%) included vitamin D.

- Ten or 20 years ago it was “state of the art” to just use a calcium supplement with vitamin D. Then we learned that the blood level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (the active form of vitamin D in the bloodstream) did not necessarily reflect vitamin D intake from the diet. In today’s world a study in which the 25-hydroxy vitamin D level is not measured should be considered sub-standard.

- Only 18 (35%) of the studies measured baseline 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels.

- If dietary calcium intake at baseline is already adequate, it is illogical to expect additional calcium to significantly increase bone density.

- The baseline calcium intake was <800 mg/day (clearly inadequate) in only 26 (51%) of the studies. Baseline calcium intake was either not determined in the other studies or was already in the adequate range prior to supplementation.

- In the future, we will probably want to include exercise as a component in the study (more about that next week). None of the studies included exercise as a component

In short, by today’s standards many, if not most, of the studies included in the meta-analysis had an inadequate design.

If I had designed the meta-analysis, I would have been a lot more restrictive in the studies I included.

- I would have started by including only studies in which the baseline intake of calcium was <800 mg/day. If you want to critically evaluate whether calcium supplementation has a beneficial effect, you need to start with people who have an inadequate dietary intake of calcium. If their diets are already calcium sufficient, supplementation is unlikely to have any benefit.

- At the very least I would only include studies that used calcium supplements containing 400-800 IU of vitamin D as well. In fact, based on the latest data, I would make sure that the calcium supplement I used also contained adequate levels of magnesium, vitamin K, zinc, copper and manganese. All of those have been shown to be important for bone formation and we cannot assume they are present at sufficient levels in their diet (more about that next week).

- I would only include studies that measured blood levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D at baseline and following supplementation with vitamin D so that we knew that the 25-hydroxy vitamin D level was sufficient to support optimal calcium utilization.

- Finally, I would only include studies that specifically measured the effect of exercise on calcium utilization or included exercise as an integral part of their study.

The number of studies included in the meta-analysis would be much less, but they would all be high quality studies.

Finally, the authors also noted that a number of studies in the supplement group showed significantly greater (2.5 – 5.0%) increase in bone density. They dismissed them as outliers. I would have preferred a closer look at those studies to see if there was anything about the population group or study design that might explain the greater bone density increase in those studies.

Apples and Oranges

Because the authors included a wide variety of clinical studies, they were able to state that “Increases in bone mineral density were similar in trials of calcium monotherapy [calcium by itself] versus co-administered calcium and vitamin D…and in trials where baseline dietary calcium intake was <800 [clearly insufficient] versus >800 [probably sufficient] mg/day.” This could be considered a strength of their meta-analysis, but they are only valid comparisons if other important features of the studies being compared were uniform – i.e. they were comparing apples to apples.

Because the authors included a wide variety of clinical studies, they were able to state that “Increases in bone mineral density were similar in trials of calcium monotherapy [calcium by itself] versus co-administered calcium and vitamin D…and in trials where baseline dietary calcium intake was <800 [clearly insufficient] versus >800 [probably sufficient] mg/day.” This could be considered a strength of their meta-analysis, but they are only valid comparisons if other important features of the studies being compared were uniform – i.e. they were comparing apples to apples.

But what if they were comparing apples and oranges?

For example, we know that vitamin D is required for efficient calcium utilization. When the authors compared studies having a baseline calcium intake of <800 mg/day with studies having a baseline calcium intake of >800 mg/day, they did not even check to see whether use of vitamin D was evenly distributed between the two groups. If most of the studies with a baseline calcium intake of <800 mg/day did not include vitamin D with their calcium supplements, the authors would be comparing apples and oranges. The comparison would be invalid.

Similarly, we also know that if calcium intake at baseline is adequate, adding more calcium is unlikely to increase bone density significantly. When the authors compared studies with and without vitamin D, they did not even check to see whether baseline calcium intake was evenly distributed between the two groups. If the participants in most of the studies utilizing supplements providing both calcium and vitamin D were already consuming sufficient calcium at baseline, they would be comparing apples to oranges. Again, the comparison would be invalid.

The authors of the meta-analysis simply did not provide the detail needed to determine whether their comparisons were apples to apples or apples to oranges. Thus, what seemed to be a strength of their study is actually a major weakness.

The Bottom Line

- A recent study has reported that the RDA recommendation of 1,000 – 1,200 mg/day of calcium for people over 50 provides only a minimal increase in bone density (0.7-1.8%) over the first year or two. This translates into a very small (5-10%) decrease in risk of bone fractures. It did not matter whether the calcium came from dietary sources or from supplementation. The authors concluded that adding extra calcium to the diet, whether from food or supplements, was not a very efficient way to increase bone density and prevent fractures.

- This study suffers from some serious flaws. It is a meta-analysis of previous clinical trials looking at the effects of calcium on bone density. Meta-analyses can be very strong studies because they average the effects of many individual studies. However, meta-analyses can also suffer from the “garbage-in, garbage-out” phenomenon. Simply put, the quality of the meta-analysis is only as good as the studies that go into it. In this case the meta-analysis included many clinical studies that were done 10, 20, 30 and even 40 years ago. Based on what we now know about bone metabolism, the design of many of those early studies was clearly inadequate (details are given in the article).

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This information is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease.