Subscribe To Our Newsletter And Get 2 Free eBooks

Our Mission

“Health Tips from the Professor” is dedicated to providing busy professionals with cutting edge health information in a way that is both scientifically accurate and understandable. Our goal is to keep you abreast of the latest developments in health, nutrition and fitness. We will cut through the sensational headlines and hype to let you know what information you can trust, and we will provide you with this information in a straight-forward manner so that you can apply it to your personal health goals.

Most Read Articles From Dr. Steve Chaney

Latest Article

The Low Carb Myth

Posted April 8, 2025 by Dr. Steve Chaney

The “Goldilocks Effect”

Author: Dr. Stephen Chaney

The low carb wars rage on. Low carb enthusiasts claim that low-carb diets are healthy. And they claim the lower you go, the healthier you will be. Let me start with some definitions:

The low carb wars rage on. Low carb enthusiasts claim that low-carb diets are healthy. And they claim the lower you go, the healthier you will be. Let me start with some definitions:

- The typical American diet is high carb. It gets about 55% of its calories from carbohydrates. [Note: The Mediterranean and DASH diets also get about 55% of their calories from carbohydrates. I’ll talk more about that later.]

- Moderate carb diets get 26-46% of their calories from carbohydrates. Examples include the low carb Mediterranean diet and the Paleo, South Beach, and Zone diets.

- Low carb diets get <26% of their calories from carbohydrates. The Atkins diet is the classic example of a low carb diet.

- Very low carb diets get <10% of their calories from carbohydrates. Examples are the Keto and Carnivore diets.

And I don’t need to tell you that the Keto and Carnivore diets are receiving a lot of favorable press lately.

But some health experts warn that low carb and very low carb diets may be dangerous. Several studies have reported that low carb diets increase the risk of mortality (shorten lifespan).

As a consumer you are probably confused by the conflicting claims. Are low carb diets healthy, or is this another myth? In this issue of “Health Tips From the Professor” I am going to discuss two very large studies that came to opposite conclusions.

Both were what we call meta-analysis studies. Simply put, that means they combine the data from several smaller studies to obtain more statistically reliable data. But as Mark Twain said, “There are lies. There are damn lies. And then there are statistics.”

The first study, called the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study, was published a few years ago. It included data from 135,335 participants from 18 countries across 5 continents. That’s a very large study, and normally we expect very large studies to be accurate.

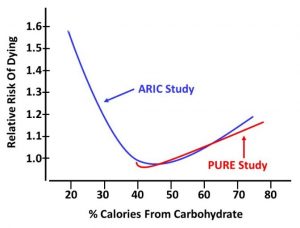

It showed a linear relationship between carbohydrate intake and mortality. Simply put, the more carbohydrate people consumed, the greater their risk of premature death. The results from the PURE study had low carb enthusiasts doing a victory lap and claiming it was time to rewrite nutritional guidelines to favor low carb diets.

Whenever controversies like this arise, reputable scientists are motivated to take another look at the question. They understand that all studies have their weaknesses and biases. So, they look at previous studies very carefully and try to design a study that eliminates the weaknesses and biases of those studies. Their goal is to design a stronger study that reconciles the differences between the previous studies.

And this study had two glaring weaknesses.

- The percent carbohydrate intake ranged from 40% to 80%. It showed that a moderate carbohydrate intake might be healthier than a high carbohydrate intake, but it provided no information about low carb or very low carb diets.

- The data was primarily from Asian countries. It was not clear whether it was relevant to the kind of diets consumed in North America and Europe.

A second study published a year later (SB Seidelmann et al, The Lancet, doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30135-X eliminated these weaknesses and resolved the conflicting data.

How Was The Second Study Done?

This study was performed in two parts. This first part drew on data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. That study enrolled 15,428 men and women, aged 45-64, from four US communities between 1987 and 1989. This group was followed for an average of 25 years, during which time 6283 people died.

This study was performed in two parts. This first part drew on data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. That study enrolled 15,428 men and women, aged 45-64, from four US communities between 1987 and 1989. This group was followed for an average of 25 years, during which time 6283 people died.

Carbohydrate intake was calculated based on food frequency questionnaires administered when participants enrolled in the study and again 6 years later. The study evaluated the association between carbohydrate intake and mortality.

The second part was a meta-analysis that combined the data from the ARIC study with all major clinical studies since 2007 that measured carbohydrate intake and mortality and lasted 5 years or more. The total number of participants included in this meta-analysis was 432,179, and it included data from previous studies that claimed low carbohydrate intake was associated with decreased mortality.

The Low Carb Myth

The results from the ARIC study were:

The results from the ARIC study were:

- The relationship between mortality and carbohydrate intake was a U-shaped curve.

-

- The lowest risk of death was observed with a moderate carbohydrate intake (50-55%). This is the intake recommended by current nutrition guidelines.

-

- The highest risk of death was observed with a low carbohydrate intake (<20%).

-

- The risk of death also increased with very high carbohydrate intake (>70%).

- When the investigators used the mortality data to estimate life expectancy, they predicted a 50-year-old participant would have a projected life expectancy of:

-

- 33.1 years if they had a moderate intake of carbohydrates.

-

- 4 years less if they had a very low carbohydrate intake.

-

- 1 year less if they had a very high carbohydrate intake.

- The risk associated with low carbohydrate intake was affected by what the carbohydrate was replaced with.

-

- When carbohydrates were replaced with animal protein and animal fat there was an increased risk of mortality on a low-carb diet.

The animal-based low-carb diet contained more beef, pork, lamb, chicken, and fish. It was also higher in saturated fat.

-

- When carbohydrates were replaced with plant protein and plant fats, there was a decreased risk of mortality on a low-carb diet. The plant-based low-carb diet contained more nuts, peanut butter, dark or whole grain breads, chocolate, and white bread. It was also higher in polyunsaturated fats.

- The effect of carbohydrate intake on mortality was virtually the same for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and non-cardiovascular mortality.

- There was no significant effect of carbohydrate intake on long-term weight gain (another myth busted).

The results from the dueling meta-analyses were actually very similar in some respects. When the data from all studies were combined:

- Very high carbohydrate diets were associated with increased mortality.

- Meat-based low-carb diets increased mortality, and plant-based low-carb diets decreased mortality.

- The results were the same for total mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and non-cardiovascular mortality.

The authors concluded: “Our findings suggest a negative long-term association between life-expectancy and both low carbohydrate and high carbohydrate diets…These data also provide further evidence that animal-based low carbohydrate diets should be discouraged.

Alternatively, when restricting carbohydrate intake, replacement of carbohydrates with predominantly plant-based fats and proteins could be considered as a long-term approach to healthy aging.”

Simply put, that means if a low carb diet works best for you, it is healthier to replace the carbs with plant-based fats and protein rather than animal-based fats and protein.

The “Goldilocks Effect”

This study also resolved the discrepancies between previous studies. The authors pointed out that the PURE study relied heavily on data from Asian and developing countries, and the average carbohydrate intake is very different in Europe and the US than in Asian and developing countries.

This study also resolved the discrepancies between previous studies. The authors pointed out that the PURE study relied heavily on data from Asian and developing countries, and the average carbohydrate intake is very different in Europe and the US than in Asian and developing countries.

- In the US and Europe mean carbohydrate intake is about 50% of calories and it ranges from 25% to 70% of calories. With that range of carbohydrate intake, it is possible to observe the increase in mortality associated with both very low and very high carbohydrate intakes.

- The US and European countries are affluent, which means that low carb enthusiasts can also afford diets high in animal protein.

- In contrast, white rice is a staple in Asian countries, and protein is a garnish rather than a main course. Consequently, overall carbohydrate intake is greater in Asian countries and very few Asians eat a truly low carbohydrate diet.

- High protein foods tend to be more expensive than high carbohydrate foods. Thus, very few people in developing countries can afford to follow a very low carbohydrate diet, and overall carbohydrate intake also tends to be higher in those countries.

Therefore, in Asian and developing countries the average carbohydrate intake is greater (~61%) than in the US and Europe (~50%), and the range of carbohydrate intake is from 45% to 80% of calories instead of 25% to 70%. With this range of intake, it is only possible to see the increase in mortality associated with very high carbohydrate intake.

In fact, when the authors of the current study overlaid the data from the PURE study with their ARIC data, there  was an almost perfect fit. The only difference was that their ARIC data covered both low and high carbohydrate intake while the PURE study touted by low carb enthusiasts only covered moderate to high carbohydrate intake.

was an almost perfect fit. The only difference was that their ARIC data covered both low and high carbohydrate intake while the PURE study touted by low carb enthusiasts only covered moderate to high carbohydrate intake.

[I have given you my rendition of the graph on the right. If you would like to see the data yourself, look at the paper.]

Basically, low carb advocates are telling you that diets with carbohydrate intakes of 26% or less are healthy based on studies that did not include carbohydrate intakes below 40%. That is misleading. The studies they quote are incapable of detecting the risks of low carbohydrate diets.

In short, the ARIC study finally answered the question, “How much carbohydrate should we be eating if we desire a long and healthy life?” The answer is “Enough”.

I call this “The Goldilocks Effect”. You may remember “Goldilocks And The Three Bears”. One bed was too hard. One bed was too soft. But one bed was “just right”. One bowl of porridge was too hot. One was two cold. But one was “just right”.

According to this study, the same is true for carbohydrate intake. High carbohydrate intake is unhealthy. Low carbohydrate intake is unhealthy. But moderate carbohydrate intake is “just right”.

What Does This Study Mean For You?

There are several important take-home lessons from this study:

There are several important take-home lessons from this study:

1) All major studies agree that very high carbohydrate intake is unhealthy. In part, that reflects the fact that diets with high carbohydrate intake are likely to be high in sodas and sugary junk foods. It may also reflect the fact that diets which are high in carbohydrates are often low in plant protein or healthy fats or both.

2) All studies that cover the full range of carbohydrate intake agree that low and very low carbohydrate diets are also unhealthy. They shorten the life expectancy of a 50-year-old by about 4 years.

3) The studies quoted by low carb enthusiasts to support their claim that low-carb diets are healthy don’t include carbohydrate intakes below 40%. That means their claims are misleading. The studies they quote are incapable of detecting the risks of low carbohydrate diets. Their claims are a myth.

4) Not all high carb diets are created equally. As I noted above, the Mediterranean and DASH diets are just as high in carbohydrates as the typical American diet, but their carbohydrates come from whole fruits and vegetables, whole grains, beans, nuts, and seeds. And multiple studies show that both diets are much healthier than the typical American diet.

5) Not all low carb diets are created equally. Meat-based low-carb diets decrease life expectancy compared to the typical American diets while plant-based low carb diets increase life expectancy.

6) The health risks of meat-based low-carb diets may be due to the saturated fat content or the heavy reliance on red meat. However, the risks are just as likely to be due to the foods these diets leave out – typically fruits, whole grains, legumes, and some vegetables.

7) Proponents of low-carb diets assume that you can make up for the missing nutrients by just taking multivitamins. However, each food group also provides a unique combination of phytonutrients and fibers. The fibers, in turn, influence your microbiome. Simply put, whenever you leave out whole food groups, you put your health at risk.

The Bottom Line

The low-carb wars are raging. Several studies have reported that low carb diets increase risk of mortality (shorten lifespan). However, a study published a few years ago came to the opposite conclusion. That study had low carb enthusiasts doing a victory lap and claiming it is time to rewrite nutritional guidelines to favor low-carb diets.

However, a study published a year later resolves the conflicting data and finally answers the question: “How much carbohydrate should we be eating if we desire a long and healthy life?” The answer is “Enough”.

I call this “The Goldilocks Effect”. According to this study, high carbohydrate intake is unhealthy. Low carbohydrate intake is unhealthy. But moderate carbohydrate intake is “just right”.

Specifically, this study reported:

- Moderate carbohydrate intake (50-55%) is healthiest. This is the carbohydrate intake found in healthy diets like the Mediterranean and DASH diets, and is the intake recommended by current nutritional guidelines.

2) All major studies agree that very high carbohydrate intake (60-70%) is unhealthy. It shortens the life expectancy of a 50-year-old by about a year.

3) All studies that cover the full range of carbohydrate intake agree that low carbohydrate intake (<26%) is also unhealthy. It shortens the life expectancy of a 50-year-old by about 4 years.

4) The studies quoted by low carb enthusiasts to support their claim that low-carb diets are healthy don’t include carbohydrate intakes below 40%. That means their claims are misleading. The studies they quote are incapable of detecting the risks of low carbohydrate diets.

5) Meat-based low-carb diets decrease life expectancy compared to the typical American diet while plant-based low carb diets increase life expectancy. This is consistent with the results of previous studies.

The authors concluded: “Our findings suggest a negative long-term association between life-expectancy and both low carbohydrate and high carbohydrate diets…These data also provide further evidence that animal-based low carbohydrate diets should be discouraged.”

Simply put, the latest study means that the supposed benefits of low carb diets are a myth.

For more details, read the article above.

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This information is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease.

______________________________________________________________________________

My posts and “Health Tips From the Professor” articles carefully avoid claims about any brand of supplement or manufacturer of supplements. However, I am often asked by representatives of supplement companies if they can share them with their customers.

My answer is, “Yes, as long as you share only the article without any additions or alterations. In particular, you should avoid adding any mention of your company or your company’s products. If you were to do that, you could be making what the FTC and FDA consider a “misleading health claim” that could result in legal action against you and the company you represent.

For more detail about FTC regulations for health claims, see this link.

https://www.ftc.gov/business-guidance/resources/health-products-compliance-guidance

______________________________________________________________________

About The Author

Dr. Chaney has a BS in Chemistry from Duke University and a PhD in Biochemistry from UCLA. He is Professor Emeritus from the University of North Carolina where he taught biochemistry and nutrition to medical and dental students for 40 years. Dr. Chaney won numerous teaching awards at UNC, including the Academy of Educators “Excellence in Teaching Lifetime Achievement Award”. Dr Chaney also ran an active cancer research program at UNC and published over 100 scientific articles and reviews in peer-reviewed scientific journals. In addition, he authored two chapters on nutrition in one of the leading biochemistry textbooks for medical students.

Since retiring from the University of North Carolina, he has been writing a weekly health blog called “Health Tips From the Professor”. He has also written two best-selling books, “Slaying the Food Myths” and “Slaying the Supplement Myths”. And most recently he has created an online lifestyle change course, “Create Your Personal Health Zone”. For more information visit https://chaneyhealth.com.

For the past 53 years Dr. Chaney and his wife Suzanne have been helping people improve their health holistically through a combination of good diet, exercise, weight control and appropriate supplementation.